Thursday, 16 – 02 – 2006

We arrived this afternoon and the reversing mechanism of the Endless Sea was still being repaired.

There were doubts about what had broken the fitting disc, twisted the reversing axle and damaged many other smaller pieces like what happened on our way from Amapa to Belem. Some sort of systemic mistake was causing the same problem again and I was not satisfied with the explanations I had been given. While I was preparing my stuff to go Bahia’s Federal University, I called the manufacturer in the interior of the state of São Paulo, ZF, complaining about the diagnosis Salvador’s representative had given to me. I was tough with him. I promised “to use all my rights” to have the service they were supposed to offer. I was paying a lot of money for that sort of repair. I had the right to require the repair services of the manufacturer’s representative since the slightest mistake in the fitting might mean a broken mechanism again. Besides, it was the second time it had happened during the trip which is unusual. To solve the problem once and for all they were supposed to be meticulous.

I hung up the phone and rushed to Bahia’s Federal University. We had arranged two appointments. The first one with biologist, Miguel Accioly, who participated among other things in BMLP – Brazilian Program of Crustacean Culture Interchange – which took place from 1996 to 2001, involving five Brazilian universities and three from Canada. Each country should have contributed with 50% of the funds. However, as Accioly said, “only the Canadians gave money”. According to him, it was a pity seeing that “the program was very good, but it was impossible to have a dialogue with the government.”

I told him I was disappointed since from Amapa to the point where I was, I had only seen the devastation caused by the crustacean culture. Apart from incipient experiences such as the alga breeding in Fleixeiras, Ceara, the oyster farm in Pirambu, Sergipe, there was almost nothing. Professor Accioly told us about a sururu breeding, a type of mollusk, in Maranhao, and bijupira breeding here in Bahia, a fish which has been increasingly demanded in the international market. But in general he agreed it was very little for such a long coast with so many different ecosystems. According to him, there is no lack of researches in universities, but we must turn them into public policies by applying them in coastal traditional communities which very often are extremely poor and have to face the overfishing problem, the decreasing variety of species and shoals. “The government doesn’t like poor people, only businessmen,” summarizes Accioly. Then he gave us an example: the native shrimp breeding in cages which causes no environmental damage and was developed by Bahia’s Federal University and was successfully used in Mexico, “since it was supported by the Mexican government, unlike here.”

Another similar case was Cuba’s. This country was interested in the oyster culture developed by the same university and it is being implanted successfully. In Brazil, authorities seem to prefer to please a few powerful politicians and businessmen by facilitating their lives as well as their huge shrimp farms; sometimes they even change the state environmental law, like in Bahia, to justify undertakings such as Lusomar.

Professor Accioly, said ironically: “The crustacean culture is more profitable than planting marijuana in the Northeast. There are two, three harvests per year. The breeding land is not yours, you don’t have to spend a dime to buy it, and it is public area. Just a few workers are necessary and part of them are underemployed with no rights. Ok, it lasts 4, 5 or 6 years, then we’ll see what has to be done to recover the area”.

Actually, he is right, this is the only thing that justifies what we saw in the Northeast, all the way from Piaui, where breeding farms are found in the Parnaiba’s Delta, to Bahia, the last state of the Northeast.

Miguel Accioly also mentioned the other plague that devastates the Northeast and he started to complain about the resorts. He cannot accept this aggressive type of huge buildings with architectural styles that have nothing to do with the local tradition, changing the landscape and isolating guests from the communities. Some entrepreneurial groups bring invasive species and put in lakes such as carps used by a few hotels in their internal areas so that foreigners who come to our country continue to enjoy their own fauna and don’t find “the exotic fauna strange”.

I think that these undertakings should be built in areas which have already been devastated seeing that most coastal states have them such as Cubatão, in Santos, Sepetiba, in Rio de Janeiro, and a few islands in Bahia, or even part of the continent, but near areas which are used by the petrochemical pole or similar ones. Since tourists don’t leave the walls of the hotels, why damaging paradise like landscapes which haven’t been submitted to human interference yet? This idea may sound radical, and in fact it is, but that’s how I feel when I see these buildings in intact areas.

Accioly talked about many other issues, especially about the difficulties concerning the intensive alga breeding whose world’s trade is in the hands of an oligopoly which controls prices. He also mentioned problems concerning the oyster breeding with native species since it is impossible to distinguish the seeds. They are always collected in mangrove areas, but there are several different species, “even one from Africa, probably introduced during the slavery period.” Thus the producer has a good harvest the first time, but next time he collects seeds “when he chooses others of a different type he may fail.” Then he jumps to the following conclusion: “the technology is not good enough to reproduce seeds in a laboratory. And those from the fields are aleatory, that’s the reason why it is difficult from one harvest to the other.”

I took advantage of professor Accioly’s expertise to understand more clearly a story which was not “well told”. When I interviewed Max Stern from Bahia Pesca I couldn’t swallow his enthusiasm when he talked about one of his projects, the tilapia breeding in estuaries. I was astonished when I saw Max talking enthusiastically about high productivity, trying to imagine how harmful that invasive species could be in Bahia’s mangroves. Now he could elucidate my doubts.

Miguel Accioly is not an enthusiast; he has already studied this issue. He suggests that behind this initiative of the government there are NGOs supported by very powerful companies and businessmen from the mining and petrol fields whose activities are not very well seen by local communities, consequently their image has to be improved, He says that the communities which are involved think that this activity is self-sustainable, but it isn’t. Accioly studied the figures and didn’t find data concerning the alevins’ acclimatization to salinity, a relatively expensive process, since the fish are both from Africa and fresh water. He explains how it works: “Reproduction occurs in cages, then biologists take the alevins and put them in tanks in laboratories with different salinization so that they adapt themselves little by little. It costs a lot, however these figures are not shown.”

Apart from this detail, this activity is environmentally harmful since tilapia is like a plague “a very strong competitor which expels native species and occupies their niches.” Besides they are strong and stand hard conditions, multiply very fast and their ration is cheap. In regard to productivity the result is always very high, but cost is not low and there are real environmental damages. Accioly suggested that during our visit to a farm that we investigate the native species that disappeared after the tilapia breeding started. This is what we will do in Camamu. We talked to Max Stern’s people who gave us the right contact in that area. We’ll see.

Afterwards, we interviewed a coral expert from the same university, Zelinda Leão. We had to record it since we are going to go Abrolhos soon, Brazil’s richest coral bank.

At the end of the day we returned to the boat. Then, I noticed my complaints were successful. The company’s management staff was waiting for me to make sure everything was all right. The reversing mechanism was brand new. They will be in charge of reinstalling it.

They repaired it correctly. When they started their work, they noticed that the wheel, the final part of the motor where the reversing gear is fit was not “correctly fixed”. If the equipment had been installed in that condition, it would be broken again. A new one was bought, and then the whole sequence of pieces was mounted. Now this problem is over. It is better.

Friday, 17 – 02 – 2006.

At 9 a.m., after breakfast, I was on the cockpit ready for the interview with Tribuna da Bahia’s journalists. We talked for an hour about our trip and the problems we have seen in regard to the occupation of the coast. Then we went to Ibama’s headquarters, in order to interview Julio Cézar de Sá da Rocha, Executive Manager.

It was a long talk. Julio didn’t omit anything either, he mentioned all Bahia’s coastal problems and showed us the perspective of someone who is in the public system and experiences all the inevitable conflicts. In regard to the resorts he said that the state encouraged the Spanish (from Iberostar, see logbook nº 15), not only by bringing them here but also by providing them with an environmental permit and showing the area where they could build, just in front of Papa-Gente lagoon, one of the most important of Fort Beach. Ibama embargoed it and a big conflict resulted from that. Julio said that he was accused of abuse of authority, however Ibama insisted: “the undertaking refused to sign a commitment agreement with mitigating measures concerning the activity.” Afterwards, the Spanish group started to build about two kilometers northwards.

I asked who was in charge of the coastal occupation and the tangle of the Brazilian legislation and the issue of various courts of appeal emerged. According to Julio, today 90% of the permits are provided by state authorities. Ibama is in charge of regional or federal cases as well as those which permit activities in Federal properties such as the maritime area. He asks: does Ibama have to be in charge of activities at the beach? No, of course not. The district has to deal with that, and in case there is no environmental agency, which occurs most of the time, state authorities decide on the issue.

“We are against crustacean culture in mangroves and apicum (a mangrove’s neighboring area considered as part of it) because of the damages it causes. Nevertheless, the undertaking is authorized by state or district authorities who don’t require Ibama’s permission, but they should. The only thing we can do is to fine them. That’s what we did with Lusomar. However, the Justice Department released it from the fine in spite of having shown an overdue permit.”

Julio explained to us that it is Ibama’s duty to regulate activities which involve more than one state, to issue permits for nuclear activities, petrol extraction, native or military land as well as activities involving regional or national impact. He also admitted that this institute has limits even in regard to these duties.

State authorities are in charge of the activity when it involves more than two districts or when one of them has no environmental agency.

On my analysis of the occupation of the coast, he said: “You have the right to be terrified, but it is all about conflict of interests. Many times the district which lacks of economic activities ends up approving the undertaking even when it has not the power to do so.”

As far as Bahia is concerned, Julio says that the colonel type of politics reigns here. “There is a patrimonial tradition. The public sector controls the private and this makes things even worse.” This is the reason why Ibama’s strategy is attacking the big fishes. “We fine Lusomar, Iberostar and the State itself.”

He concludes: “Dealing with the environmental issues means dealing with big issues and we have limits.”

We also talked about other areas of Bahia’s coast which are aimed for tourism, real estate speculation or the crustacean culture. He told us that Ibama fined 25 commercial houses in Morro de São Paulo after having inspected 27 of them. Julio says that some hotels on Morro’s second and third beaches will have to move because they were built in forbidden areas. I haven’t seen any demolition on the coast so far. They promise there will be demolition here, as well as in Mamangua, in Parati, Rio de Janeiro. I want to see if they are brave enough to do so. If they had been strict from the very beginning, the situation wouldn’t be as critical as it is today.

When Julio talks about conflicts, he says there will probably be one soon. It is about the choice made by government authorities concerning Caravelas as one of the poles of crustacean culture in Bahia, it is “Abrolho’s neighboring area”. To be able to control it, Ibama will suggest to turn the area into an extraction reserve “which has laws and rules that limit the process.” He finally says: “It is not easy to put oneself in an opposing position against business interests, especially when they are shared by the government.”

In spite of all the problems, Julio is optimistic. He acknowledges that “the capitalist logic has very little to do with environmental protection”, nevertheless he thinks we make progress. The historical process is slow, he says. He is proud of an agreement he made so that the federal police acts in the ocean, more precisely in Abrolhos, since Ibama “has no boats for inspection, we are not prepared to deal with the important coastal biome.

A significant part of the morning was devoted to the interview, then we went shopping at the supermarket as usual, we fueled, bought gasoline for the stern motor, filled our tanks with fresh water and put ice in the fridge. We were ready to leave. But we still didn’t know if they had finished repairing the motor.

As soon as we arrived, we noticed they hadn’t finished it yet. We had to align the sailboat motor which was left for the following day, nothing could be done. It was dark, time to relax and rest…

Saturday, 18 – 02 – 2006.

As soon as the last mechanic left the boat, we cast off and started to sail. We will go to the furthest part of All Saints Bay, to Aratu’s sub-bay, where one of the first petrochemical poles (from Petrobras’ post era) was established more than 50 years ago. Last time, because of the reversing mechanism problem, we couldn’t shoot in the area. We intend to do that today. Unfortunately, our work on board was longer than we had predicted, so we will have to sleep in the bay. We won’t be able to go to Morro de São Paulo as I expected. At the end of the day, when there was enough light, we entered in Aratu, before we passed by Brazil’s Navy Nautical Base. It is amazing to see that in spite of all the occupation, countless ports, petrol refinery, big and small shipyards, dozens of companies, and three million inhabitants in Salvador, the water of the All Saints Bay is still relatively clean. Fortunately, All Saints Bay is big: a surface of one thousand, one hundred square kilometers by a perimeter of 200 km, and all that with a tide that is significantly intense. This is the reason why the bay is “washed” every day. Although there are points of pollution, it is far from being compared with the bay of Santos or that of Rio de Janeiro. Good for the Baianos and all of us.

Tonight we will sleep alongside Mare Island, it is almost in front of Aratu’s bay. Tomorrow morning we will sail to Madre de Deus Island, near here, to shoot this Gulf’s second largest port terminal. Then we will sail to Morro de São Paulo.

Sunday, 19 – 02 – 2006.

After breakfast, with coffee always in the thermos bottle, invariably made by Alonso as soon as the day breaks, we went towards Madre de Deus. This island is about 6 miles away from Mare Island. But to go there, we have to leave as if we were going towards the sea, and many miles further, cross the south end of Mare Island then sail to Madre de Deus. All this long way to avoid the sand bars of the area. An hour and a half later we arrived there. The first thing you see is the huge terminal where boats anchor, Petrobras’ petrol and gas storage facilities and a flour warehouse. As soon as we arrived, huge tug boats passed by, four or five, big and nice. Their work consists of helping other vessels, that’s why the tugs’ crew has a sort of charisma like firemen, but this is done in the sea.

Frade’s Island is in front of Madre de Deus and the space between them is like a mouth of a river. It is surrounded by beautiful islands with white sand and coconut trees behind. If you go further to the interior, you see the hill covered by Atlantic Forest. It is an exuberant place for a port. It is so beautiful that ecotourism might be offered instead. At the north end of Frade’s Island there is an extremely beautiful little church, Loreto’s built in the 17th century (see picture). Sailing a little bit further, we passed by Bom Jesus Island and arrived at the end where the village is. There in the middle of a square surrounded by colorful flamboyants, a beautiful colonial church stands out against the landscape (see pictures). Do you want more?

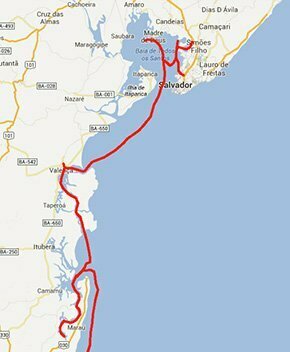

We shot every square centimeter of these beauties which surrounded us and from the port in the middle of that amazing landscape. Afterwards we started sailing 40 miles towards Morro the São Paulo, at the south end of All Saints Bay. We sailed for a long period of time in the bay; we went alongside the southeast coast of Itaparica until we reached the sea and went southwards. The wind was southeast of 15, 17 knots coming sideways which helped the Endless Sea to sail free, nicely, taking segment and slipping as if it were a huge locomotive going down a long and smooth slope. At the end of the day, we were anchored in front of the Lighthouse of Morro de São Paulo, behind the hill whose name was given to that place, protected from the wind and the waves. We had a wonderful evening, a soft breeze and a sky full of stars. In moments like this, I think how good it is to do what one likes and to be paid to be in such fantastic places like the one we are now.

Tonight we will sleep like babies.

Monday, 20 – 02 – 2006.

We left the boat early to see how the occupation of this fashionable area has occurred. It couldn’t be different. The fortress, used in the first centuries to protect Salvador from the boats coming southwards or to watch and guard the entrance of important villages such as Valença and Cairu, has become a tourism point. There are pousadas everywhere, fortunately respecting local features, they are neither extremely big, nor extremely exotic architecturally speaking. You can hardly see them. But all the shops that come with them, restaurants, supermarkets, pharmacies, etc, are in a keen competition. The same process that devastated Fort Beach is seen here, it is very densely occupied for local possibilities. Some houses and shops were built three steps away from the sea, not three hundred meters according to CONAMA’s resolution, and there is hardly any distance between them. Hotels bring parasols and the beaches are full of them, which doesn’t give you any perspective. On the shore, there are coral banks near the beaches and altogether it is amazingly beautiful; a lot of tourists walk from one side to the other. It is difficult to find Brazilians among them… When we walked around, we saw lots of garbage on the beaches which proves that public authorities didn’t inspect the occupation. A few meters further, we crossed a bridge and under it there was a thin thread of black, liquor like, fetid water flowing on the beach in a zigzag line leading to the sea. It is obviously waste left by visitors.

When we were returning to the boat, we saw summer houses at the top of the hill where everybody knows it is forbidden to build since when you do it, the vegetation has to be cut. Then it is just a matter of time, the erosion resulting from the rain comes and the land slides with very bad consequences. It was almost 11 a.m. when we left Morro de São Paulo to go to Valença, an important city in the past which was remarkable for the 19th century manufactures. To go there, we had to leave the main riverbed and take a secondary one. It didn’t take too long for the keel touch the muddy bottom. We anchored and took the small rubber boat. Valença was built on the river bank, in this huge lagoon where Morro de São Paulo, Cairu and other important cities are. They emerged on the way between the islands Boipeba and Tinhare and which leads to Camamu bay. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Portuguese from Bahia’s central government, used to come here in search of wood for their ships taken to India. This was the focus of the economy of those times. Valença is a beautiful city with bridges that remind us of Venice. At the end of the afternoon we returned to the Endless Sea where Alonso was and went to Cairu, just a few miles away. We anchored in front of the village and went to bed. Tomorrow we will shoot many things around.

Tuesday, 21 – -2 – 2006.

I was in the cockpit where there is always a refreshing breeze. Here, inside, where I write sitting at the plotting table, it is very often extremely hot. After writing about the activities of the day, I go to the deck, I smoke a cigarette (yes, unfortunately, I smoke), I hear the singing of locusts from the forest, I see a huge amount of stars, in a night anyone would call dazzling, and I return to continue.

It was raining when I woke up this morning. The stern cabin, that’s where we sleep, has a hatchway right above where I put my face on the pillow. If there was an aim, the result wouldn’t be as good as it is. When it rains the drops fall just between my eyes. I woke up asleep and closed the window. I returned to my bed right away.

In our crew, I am the last one to wake up. Alonso is the first one to wake up at daybreak and he makes coffee. The second one is Cardozo since he sleeps in the living room and it is not protected from light. Then he wakes Agis up who, after a while, succeeds in waking me up. We have breakfast with fruits, sandwiches, tea and coffee, sometimes, pancakes, sometimes, cuscuz (prepared by Agis), juice and cereals. Then we are ready for a hard day, exposed to a lot of sun, wind and heat, but full of discoveries in one of the world’s most beautiful journeys. Now, for instance, I have just returned from the deck. Cardozo had called me to hear the breathing of the dolphins fishing around us. It was wonderful. We couldn’t see them, just hear them when they came up and the noise made by the air jet expelled after every time they dive. It is 11 p.m. and it is completely dark, we are anchored in front of Caravelas, in the Cairu River where Tinhare and Boipeba islands meet. We sailed inwards between the islands and the continent towards Camamu.

We woke up with the view of Santo Antonio Convent built in Cairu in 1630. Like most of them, this one was also built at the top of a hill standing out in the landscape, with a wide view of the river. It is a remarkable example of the Portuguese architecture here in Brazil. It is worth seeing. The ceiling of the church is hand painted; it took more than 50 years to finish. Some alters are superbly carved. There are rooms whose walls are entirely covered by tiles with mosaics which tell stories, whereas the ceiling shows different scenes painted on wood. It is magnificent, from the monumental rooms to the kitchen passing by the typical internal yard.

After lunch, at the end of the afternoon, when the sun was weaker, we took the rubber boat and sailed the 12 miles which separated us from Boipeba Island’s oceanic beaches, at the mouth of the Inferno’s River; Tinhare Island is just beside it. On the side which leads to the sea, there are beautiful beaches; on the other side leading to the continent, the banks are entirely occupied by mangroves. This results in a perfect and beautiful natural scene which is not occupied in a predatory way. I was here when tourism had just started. Ten years later, occupation is a fact, but in this case it preserved the landscape. There are barely ten pousadas which welcome tourists at different prices. All of them were built behind the first row of coconut trees, although they are not 300 meters away from the high tide according to CONAMA’s resolution. Anyway, these pousadas don’t interfere in the charming and beauty due to the fact they are behind the trees. We were amazed and enjoyed the sunset, when we eventually returned to the Endless Sea.

In the evening we left the boat to talk to the person in charge of the tilapia breeding and we were told that tomorrow morning fishes will be collected in one of the cages. We will be there to shoot it.

Wednesday, 22 – 02 – 2006.

At 6 a.m., Seu Antonio, the pilot Geni sent us, was on board the Endless Sea. Alonso left the motor for him. Then we all woke up. We had breakfast and took the rubber boat to see the tilapias being collected from the cage at Torrinhas. Beside a floating unit anchored near the row of cages, there was a fishing boat which came to carry the production. There were five or six men working on the platform. Some were putting ice in tanks as big as swimming pools, while others used the puçá (a small conic net used to fish shrimps, etc.) and took bags full of fishes which went straight to the tank. In a short period of time it was full. They repeated the operation with another one. There were four to keep all those fishes. We stood there for an hour, enough time to shoot the operation. We could even see a few fishes escaping from the puça and they almost jumped into the sea. This is the biggest problem this type of breeding causes. In a couple of years this area will probably be infested with tilapias and many of the species which swim here today will disappear. This is not wise. For the time being, local inhabitants are satisfied; we’ll see in the future. We talked to Luciano de Freitas dos Santos, president of Caravelas’ fishing cooperatives. He told us how they started six years ago. The first two years were devoted to observation and learning, then after this period the farm started to take off. Odebrecht Foundation sponsors this cooperative by giving cages, ration, alevins and technical assistance. The Foundation also gives qualifying courses. Forty-eight people have already been qualified in three villages: Caravelas, Torrinhas and ……. Every family interested in breeding receives ten cages with 900 alevins in each. After four months, when fishes are collected, the first investment is deducted, then the rest is shared the following way: a family receives 50 cents per fish. The average is five tons per collecting operation which, according to Luciano, sums up a total of 2.400,00 reais per module.

Everything is sent to Ilheus where the fish is processed, then to Salvador and from there to the final consumers. I asked professor Accioly who these consumers were, since I have never heard of tilapias for sale. He answered that I had probably already heard the “commercial” name, used in restaurants and places of the same sort: Saint Pierre. This one I know.

After the recording section, we sailed in the Cairu River for an hour southwards until we arrived in Barra do Carvalho, a bay that leads to Camamu. We crossed this creek towards Muta End, passing inside Camamu Grande Island and we continued to sail among banks not extremely occupied, but with evident signs of devastation of the Atlantic Forest. On the hills, we could see there were more pasture lands than forest on the horizon. This proves there may be many farms inwards.

We spent all day long like this. I wanted to go farther to have a good idea of the occupation, passing by Marau and reaching Cachoeiras do Tremembe, a small waterfall which would be a nice backdrop for our program.

We stopped at Marau just to leave our pilot who wanted to go back home today. But we were disappointed. There weren’t any buses going in the direction he wanted. Seu Antonio will have to sleep with us tonight. We continued for an hour and a half, then we arrived at the mouth of the river at whose end is the famous waterfall. I hope it is worthwhile; it was hard to arrive here. We will see that tomorrow.

Before leaving that area I want to pass by Cajaiba, a village which was famous because of the shipyards where Saveiros were built. If possible we’ll go to Senhinharem’s bar to see a laboratory of tilapias’ alevins. Then we will go to Itacare, our next stop.

Writing today was very difficult. As I said, we are at the farthest part of a big bay. There is barely any wind. There is very little light too, only the lamps of the sitting room of the sailboat. They also attract insects. These small winged beings that smash on the screen of my computer. Reckless and nervous, they try to fly again and hit my face and fall by hundreds on the keyboard. Many times, I give a rap on one of them before I type one of the letters. This is driving me mad. I don’t know if I concentrate on the winged beings or on the text. This is not going to work. It is better to stop.

Tuesday, 23 – 02 – 2006.

In the morning with high tide, we decided to enter with the sailboat in a small affluent at the end of which the waterfall is. At the beginning, it seemed it was not going to work. The keel was touching the muddy bottom of the riverbed. But after a hard beginning, the Endless Sea finally crossed it. We sailed until we reached the waterfall, very beautiful and we stayed there all morning. Anchoring was unnecessary since the keel was touching the bottom.

We shot, took pictures, swam a little, rested and the moment arrived: “let’s continue, we still have a long way.” We started sailing back. It was a wonderful day full of sun, strong wind and beautiful landscape on the banks. We stopped at Marau to pick up some fresh water; the Endless Sea’s tanks were almost dry. It is a drowsy village, it stopped in time, there is no agitation, too quiet for Bahia’s spirit.

An hour later, the tanks were full and we continued our way towards Campinho at the entrance of the bay where our pilot would stop. When we arrived, there wasn’t any boat. Alonso had to take him by rubber boat to Camamu, the greatest city in the area with 30 thousand inhabitants, where he would easily find a means of transportation that would take Seu Antonio home. Since the bay is low today, it is impossible to arrive in Camamu by sailboat. That’s why Alonso used the rubber boat. Before we anchored in a place as beautiful as paradise, near an island with white sand beaches (like salt), coconut trees lying on the sand and warm water around. Wonderful. We will sleep here. Tomorrow we will cross the bay and reach the village of Cajaiba do Sul, in front of where we are to shoot the shipyards and the carpenter masters who built so many beautiful and good quality traditional boats that made the city famous.

I was happy to see all this area. The first time I came here I was sailing with my first sailboat, Tiki, about twenty years ago. This area changed a little bit. Cairu, Valença’s mangroves are in good shape, it seems they are not touched by the inevitable pressures of the increasing tourism, the development of the cities and the economic pressures. Fortunately, there aren’t many shrimp farms in this area. Camamu bay is impressive. Summer houses are seen, but not too many. They are usually built without causing a lot of damage to the natural scenery. And when there are hotels or pousadas, they are not very visible. However, as I said before, where there used to be forest there is pasture. This is a very big area, near big centers, like Salvador (it is less than 60 miles northwards) and Ilheus (about 50 miles southwards) but they still resist keeping the natural beauty and part of their rich biodiversity. Good sign. We have to celebrate, in spite of the mass tourism threats and the weakness of the agencies which are in charge of the environment.

Friday, 24 – 02 – 2006.

Before midday, we lifted anchor to go to Itacaré, 22 miles at the south of Muta end which is the entrance of Camamu bay. We went to Cajaiba where we visited several shipyards which built about 15 big schooners and only three Saveiros. Two of them were quite small, like boats, and the third one of a regular size. When we talked to a carpenter, Joselito, we were told there wasn’t much interest in new Saveiros. There is very little demand. On the other hand, schooners sell so much that they don’t even wait for the order. They simply build them and end up selling them to tourism companies most of the time. Just one or two become private yachts. And the best of it is: Ibama has not been an obstacle here. Joselito was happy with the lack of inspection since last year it had caused some trouble for these professionals. I took advantage of the situation to tell him about the conversation I had had with Ibama’s manager in Salvador and the promise he made of not prohibiting naval carpenters to continue with their profession. Anyway, I gave Joselito the name and the phone number of Julio Cesar’s office, regional manager, with the explicit recommendation that if by any chance an inspector comes, they had his promise they would be free of that type of problem. Joselito thanked me a lot and repeated that all of them “leaved” (incorrectly pronounced) from that profession and it is not fair to be punished for working.

We also visited a craftsman expert in making miniatures of boats, Gilson, so skilled and ingenious that he can be considered a “naval patternmaker”, as professionals say. Gilson makes schooners with 30 and 60 centimeters and they are perfect. They are exact and faithful copies of the bigger ones. We interviewed him and I couldn’t resist and bought another Baiana canoe, with two feather type sails, all varnished, he had just made it. Beautiful. I don’t know where to put these miniatures I take to my place in São Paulo. There isn’t enough room for them. In spite of that, every time I see a new one, I can’t resist and I buy it.

Well, the sailboat is in Alonso’s hands, I adjusted myself in the cockpit, lay on a cushion on the right side where there is shade and asked to be waken up at the arrival. These moments of sailing are delicious when I can actually rest, enjoy the boat, the sailing and sleep. As soon as we arrive somewhere the “regressive count” starts: achieving goals, interviewing, searching something or someone, rushing, walking all the time under the hot sun, etc.

Saturday, 25 – 02 – 2006.

We arrived in Itacare yesterday, at the end of the day. Entering was not very easy even for us who have gone through very difficult experiences. Here we have to stay near the sea wall on the left side of the beach and enter in the small bay formed by beaches and the Contas’ River. A charming place, but very small. In the bay there is room just for four or five anchored boats. Fortunately, there were only three when we entered; two motor boats of 50 feet each and a foreign sailboat. We found room for us where we dropped anchor to spend the night. I tried to go up the Contas’ River to look for a waterfall I had seen when I came here for the first time, but we didn’t find the entrance.

Today early in the morning with cues given by fishermen we eventually arrived at the waterfall I had seen a long time ago. Now there are fences in the area with signs, litter baskets on the way, ropes which people grab to walk, and even an official entrance where every visitor pays ten reais for the ticket. There even a restaurant in the area to take advantage of the flow of tourists. It was worthwhile, anyway. The small entrance river is wonderful. It is surrounded by mangroves; there are trees full of bromelias, which usually form tunnels, and a countless number of birds. Different types of humming-birds cross the air above our heads, while kingfishers fly almost touching the water. In the middle of this exuberant scene we visited three waterfalls forming a swimming pool under them. Amazing. And it is extremely refreshing to be showered by the cold waters. None of us resisted.

It is 8 p.m. and we are here sheltered by the Endless Sea. In this evening of Carnival we walked around Itacare village and its beautiful beaches. There are three or four around the village with 12 thousand inhabitants. Concha Beach is near the center, it is a sort of semicircle right in front of the houses of the village. Tiririca Beach is a few meters southwards, famous for its perfect waves where surfing championships started to take place. Ribeira’s Beach is the last one, a little bit southwards. These beaches are short, very beautiful and surrounded by exuberant Atlantic Forest which reminds us of Ubatuba in São Paulo, but full of tourists, especially in the high season when it reaches its maximum capacity.

In the past, Itacare was a calm non-industrial fishermen village. That’s what I saw when I first came here, during a trip with the Endless Sea ten years ago. At that time there were barely six thousand inhabitants. Then the tourists came. Pousadas were built, followed by restaurants, bars and stores. Thus the small village grew.

On the banks of Contas’ River where the city was built, you see not only mangroves, as it is the rule, but also a luxurious Atlantic Forest having rivers with rapids where people go rafting, tracks in the forest that lead to fantastic waterfalls, etc. Obviously, tourism made this village grow and the number of inhabitants has almost doubled. But it hasn’t lost its main characteristics. The same aspects are kept when you come from the sea. Fortunately, buildings are inwards and they are greater in number not in height. In general they are discreet and the landscape is not ugly because of them. If you go a little bit further there are two small resorts; Txai, which is unique and 19 kilometers away going southwards, to Ilheus. Ecoresort is in the same direction 5 kilometers away from the village. Both can have from a hundred to a hundred and fifty guests. According to the driver who brought us, a Portuguese group is about to build the third resort in the south of Itacare bay, the same area where the other two are. The difference is probably the sixth star that the new one will bring and a bigger capacity. Something else is new too: now there is a coastal road here and with the raft which crosses the bay, cars can go to Marau. This is an additional appeal for tourists who come by car and a new income generator for local inhabitants who are happy with the new situation. Nature tourism brought income, increased the economy, and generated jobs especially in the field of services for visitors.

Here is the problem. An important tourism agency in São Paulo, CVC, brought mass tourism here, which is dangerous. In addition to the greater number of people having no infrastructure, most optional programs such as tracking, rafting are offered in Ilheus by the local agency which works with CVC, consequently it doesn’t boost local economy, it simply dumps lots of people in the tracks and streets of the city. In Itarare there is an outcry against mass tourism. However, most people are satisfied with the new reality which didn’t interfere in the inhabitants’ main activity, which is fishing.

This is one of Bahia’s richest areas in terms of biodiversity. Besides the coast and the sea, there is the Atlantic Forest with its amazing diversity offering 400 different types of trees in each hectare of the forest. Unfortunately, Bahia’s south area, below Ilheus, suffers a lot with the monoculture of eucalyptus which reaches the border with Espirito Santo. This is the strongest pressure. There are many reforestation companies which are established between the north of Espirito Santo and the south of Bahia. Today eucalyptuses occupy an area of 100 thousand hectares according to CRA (the agency in charge of Bahia’s environment). Environmentalists say this figure is unreal. The occupied area reaches 300 thousand hectares.

Tomorrow we will walk around here a little bit more. We will go by car to see the neighboring areas and the resorts.

Sunday, 26 – 02 – 2006.

We started our ride at 8 a.m. We hired a driver to take us to the resorts which are away from the city. We wanted to see the occupation process inwards and it is much easier by car. The forest along the road is wonderful; the height of the trees is amazing as well as the amount of different species in one single piece of land. It is dense. It is a dark live green. On the beaches, the forest and the coconut trees are mixed together. It is marvelous. We were near both resorts and we could see that Txai follows the local architectural style. The hotel is formed by small cottages surrounded by the Atlantic Forest and it is on a plateau from where the sea can be seen. The view from there is probably beautiful. There is no conflict between the landscape and the hotel, there is integration and this is another example which could and should be followed by the undertakers. Nobody has the right to damage a wonderful landscape which took years to be created, to remain unoccupied, rich in biodiversity, because of a minor selfish excuse regardless of the interests of the great majority. And these hotels in this fashionable area show that it is possible to occupy with good taste in a sustainable way without destroying it and adding value. I was happy to know it and to take pictures (see pictures).

However, on our way back to the city, we saw the presence of slums. Going inwards into the village, after the first 5 or 6 streets, there is an area, as soon as you reach the road, where you see clearly small houses made of brick one above the other with additional wings in an amazing chaos. The streets here are unpaved, unlike the rest of the village. There are no signs of waste system; the picture here is already known. It couldn’t be different. When there is fast growth, it always causes damages. The state, the district cannot invest at the same rhythm; it lacks infrastructure and those who have no privileges suffer more. In regard to Itacare there has been little damage, but there is some and it has to be mentioned.

The other problem is that all this reputation attracts new investors. Real state speculators with no scruples, who divide the areas into tiny pieces of land, build lousy houses and devalue the area. Most of them don’t offer the benefits proclaimed and their greed is devastating. This may be the beginning of the end. We saw a few plaques of condominiums on the way, enough plaques to make us feel something in the pit of our stomachs. I hope this rich and beautiful area will be kept as it is now. The community has to be organized – it seems many of them are – and put pressure on the mayor and city councils. There must be limits, rules, obligations. Otherwise, Itacare will be like Fort Beach (in the north of Bahia), Pipa (Rio Grande do Norte, Jericoacoara (Ceara) and many others, and if that happens, that’s the end. It ends before the beginning. It would be very sad.

It was 11 a.m. when we left the bay of Itacare for our last destination: Ilheus, 32 miles southwards.

There weren’t many waves because of the strong sea. Today the northeast wind blows constantly between 18 and 19 knots. Good for us since we will be sailing in the same direction of the wind and currents. Everybody on board is tired. Nobody talks too much, each one of us helps when the boat leaves, lifting the anchor, with the cables or attaching what is loose. Then we retire ourselves somewhere. Cardozo is sleeping in the waiting room, Agis in the cabin. I am here writing at the plotting table; Alonso is sitting behind the rudder (the automatic pilot is on) with his arms crossed, looking at the horizon. This constant sun, wind and heat produce a state of torpor. Everybody is lazy, it’s normal. Since there is lack of enthusiasm, let’s use the motor, the mizzen sail (the stern sail) is lifted and the genoa (the prow sail) open. The main sail is rolled up because above the boom there is an awning which gives us an essential shade. Let it be. People on board don’t feel like working today… Anyway the GPS (the satellite navigation system) shows waves going down and the Endless Sea sails at 10.6 knots. Excellent. This is the result when the wind and the current flow in the same direction: excellent speed and a “prince” sailing.

Monday, 27 – 02 – 2006.

It’s 3 p.m. and in a couple of hours we will be leaving to go to São Paulo. This time our goal was achieved, we have three rich, different programs recorded. The last part will be on Ilheus where we are anchored. Our harbor is in front of the Yacht Club in the same bay where the port is, protected by a big sea wall.

We left the boat this morning to shoot images of Ilheus Historical Patrimony and show it on TV. The city was famous because that’s where Jorge Amado was born and the streets, bars and people were several times the setting of his books, especially the classic “Gabriela, Cravo e Canela”. There is a bar called Vesuvio where Nacib (this book’s character) used to meet Gabriela, and today it is always full because of the novel, not necessarily because of its own merits. We went there. We also shot Jorge Amado’s house, a high and narrow two-storey house which is almost in front of Cine Teatro a few meters from the famous bar.

We went to the shore but the beaches in the urban area have nothing special. They are long with dark sand. A long straight strip. Before returning to pick up our stuff, we shot a few historical buildings which are well preserved. Then we had lunch at the Vesuvio. At last, we went to Bataclan, a cabaret where there were unforgettable parties sponsored by the cacao barons so richly described by Jorge Amado.

Apart from the historical importance and these buildings, Ilheus is not as interesting and beautiful as Salvador, for instance, neither does it have the typical charm of small villages such as Mangue Seco. It is neither big nor small; it has 223 thousand inhabitants living in 54 thousand houses. In regard to their health and their responsibility concerning the ocean pollution I cannot congratulate them, they are not the last in the ranking. 44% of the houses have drains and 64% have garbage collection. This and the traffic of boats and ships coming and leaving the port may be the reason why the sea water here is not as transparent as it is in Salvador. It is turbid.

I bought newspapers and magazines to be aware of what is going on around the world and the latest scandals in Brazil. Let’s see: on the front page of O Estadão a survey was published to know how many government employees occupy positions of trust in the Union, states and districts. Unbelievable: over half a million. They are those who maintain nepotism and aggravate the inefficiency of the Brazilian State. They are spread in big public companies as well as in the slightest district halls and that’s where our politicians put their wives, children, nephews, etc., to earn more money, since the money that we ordinary Brazilians pay, high taxes, is available. However, instead of using it to offer us good quality public services, we have a huge public administration which cannot guarantee even basic needs such as basic sanitation, public security and education. Many times during this journey I have made comments on the inefficiency of inspection agencies in charge of the environment as well as on the precariousness or even lack of basic sanitation in coastal states which is one of the aims of the Endless Sea Project. This is one of the reasons of this failure. Nepotism aggravates two other problems in Brazil: corruption and the inefficiency of public administration. In the article, Professor José Luiz Pagnussat from the National School of Public Administration in Brasilia says: “The worst thing is not the moral aspect. The highest price paid is every time the boss changes, the whole team is changed, and this turn over disturbs mid and long term policies. The result is inefficiency.” Professor François Bremaeker from the Brazilian Institute of District Administration (IBAM) says that “positions of trust are an open door for corruption.”

Angry and nauseous, I have a look at this week’s magazines. I read an article published by Veja whose headline is: “The forest paid PT’s bill” and the subtitle was: “CPI (Parliamentary Inquiry Committee) accuses five PT members of facilitating wood cut in exchange of money for candidates of the party.” It is written in the article that “the head of Para’s illegal deforestation, Ibama’s state executive manager, Marcilio, WAS APPOINTED TO THE POSITION BY PT CONGRESSWOMAN, ANA JULIA CAREPA, TO WHOM HE HAD BEEN MARRIED” (I wrote it in capital letters). Well, Estadão’s warning article is confirmed by Veja’s article. There is more. According to Veja, the CPI on biopirating activities, which has to do with our expedition, shows that…”part of the money given by woodcutters to get permits for illegal deforestation and wood transportation was sent to the banking accounts of the congresswoman’s advisor”. Further on, the CPI’s president, Representative Antonio Carlos Mendes Thame, states: “In spite of PT’s effort to muffle the investigations, we dismantled one of the most terrible corruption scandals in the country’s environmental area.” Seven people were accused; two Ibama’s executive managers are among them. They still occupy their positions and minister Marina Silva hasn’t said a word…

There is another interesting article which explains clearly the Brazilian problems, it is an interview published by O Estado by a brilliant and lucid economist, Eduardo Gianetti, from Ibmec. After having mentioned a long list of problems in our economy, reforms that must be carried out, he says that “high interest rates are the symptom, not the cause. The real disease of our economy reflected by the interest rates is the incapacity of investments by the Federal State to follow the cyclic increases of the demand.” He also says: “Since 1988, tax burden increased 14% of the GNP. This is Mexico’s tax burden.” He continues: “The Federal State collects from society 37% of the GNP. Additionally, there is a nominal deficit which is normally approximately 3% of the GNP, like last year’s. This means that 40% of the national income is in the public sector. The most surprising thing is that the investment capacity of the public sector is very little.”

Gianetti comments on many aspects that created this situation plus the fact that Lula’s administration hasn’t changed this picture. He concludes: “Important and painful things in the Brazilian society must change. One of them is the Social Security system, not only the INSS (National Institute of Social Security) but especially that of the public sector which has a permanent deficit resulting from the pensions paid to three million inactive people and pensioners (public employees, my parenthesis) BIGGER THAN BRAZIL’S PUBLIC EXPENSES WITH 37 MILLION CHILDREN IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS.” In other words: the Social Security deficit resulting exclusively from the three million public employees and politicians who are retired is more than the amount invested per year with 37 million children who study in public schools. It’s a nonsense, isn’t it? And Professor Gianotti concludes: “A country which commits this enormity is sentenced to permanent poverty and ignorance. Primary and secondary school have to be a priority in this country.”

As you can see, there are enough data, studies, surveys or analyses by experts. But we haven’t got enough shame, hard work and political will. It is sad, very sad, to see such a great potential thrown away since those who should be the example aren’t. They have other priorities. By the way, this week I saw in Veja other pictures of our president “who never knows anything, never sees anything.” He hasn’t been working, although a minister has recently said: “Lula hasn’t drunk for 50 days.” He is always in political campaign. Crude and using abusively his peculiar way of travestying. This time our Excellency was shown on a stand with his head covered by a northeastern bandit’s hat, surrounded by his fellows and incautious people in his endless and innocuous blah, blah, blah. Today I feel nauseous when I read the news. At every stop at the ports, I feel more and more nauseous. Even stolen money is found in the Nation’s chief advisors’ shorts.

Yes, before I forget, Paulina Chamorro sent me an email telling me about last CONAMA’s resolution passed on February 22 giving flexibility and making legal the irregular occupation of APPs, permanent preservation areas, an achievement of 1965’s Forest Code, which is now trampled on by 111 members of the Committee that approved such nonsense. It took Conama 4 years to discuss about this issue and reach this vile, electioneering and shameless verdict. It’s absurd. I will collect more data and will make more comments on it in my next logbook. I’m too sick now. I think I am going to vomit.

During our next trip we are going to Porto Seguro. If we are lucky, we will stop in Canavieiras, then enter by the mouth of the Jequitinhonha, in Belmonte. Then, in Cabralia bay, we intend to shoot Coroa Vermelha where the first mass was celebrated.

It won’t take us long to return, we need just enough time to edit these three programs. We will be back in a couple of days.