riday, 23 – 02 – 2007.

It is raining. It’s seven p.m. We are anchored at Imbituba port. A weak cold front has come and left. We haven’t had a very bad day. At 6:30 a.m., when we woke up, the horizon was clean. We lifted anchor from the pier of Veleiros da Ilha Yacht Club, where we had been very well welcomed since the end of last year, and went southwards, as usual.

Two hours later we crossed the canal which separates Santa Catarina Island from the continent, leaving Irma do Meio and Fora Islands behind and going towards the line coast. We were going to enter through Pinheira creek.

A beautiful bay continuously surrounded by a beach strip where at the north end there is a remarkable group of small dunes.

Most of this area’s water portion is used for mollusk culture. There are buoys everywhere. A few houses were built on movable areas, that is dunes. The beach is on a perfect cut of the coast line (U shaped) towards the northeast.

We sailed alongside Pinheira end and Urubu hill – both are prominent parts of the continent (on the south side) projected into the sea, with wild and uncommon forms, and then we finally arrived at the famous Guarda do Embau beach where lots of surfers go. It is a long beach with very soft sand, a few dunes behind with hills covered by vegetation around. A beautiful scenery practically unchanged.

We continued to sail. It was past 10 and northeast wind reached 18 knots. We soon arrived at Siriu, an exotic beach of savage beauty. The beach faces the open sea, with high dunes, strong waves and a sharp chain of hills behind. There is a lagoon in the interior. All this part is also unoccupied and has the same impact felt by sailors in past centuries. This coastal contour is particularly charming with bays, rocky formations, islands and cliffs, hills and mountains, one after the other. The geography of this part of Santa Catarina’s coast is particularly exuberant and creative. The diversity of unique and savage landscapes on this short way is fantastic. This is true until you reach Garopaba which is as famous and densely occupied as Porto Belo or Camboriu.

The large amount of buildings and the short distance between them is unbelievable. The occupation is so chaotic that the view from a couple of angles is astonishing. There is no infrastructure, as usual. 13 thousands inhabitants live in 3.700 private homes. Just five of them, that is 0.13% have basic sanitation (IBGE 2000).

We were in the middle of this part of our journey. We sailed alongside the coast helped by the genoa (the prow sail) and the strong northeast wind, and went to the port of Imbituba, Santa Catarina’s second most important port. Nevertheless, it is small and only has two launching cradles for medium size ships.

At about 2:30 p.m. we entered and anchored for lunch. And then we rested. Tomorrow we will have to sail 18 miles to Laguna.

It’s late now. It is past 10:00 p.m. It stopped to rain. The south wind which reached 10 knots has calmed down. It is a quiet night, perfect to end today’s day.

Saturday, 24 – 02 – 2007.

We woke up early as soon as there was daylight, but the northeast wind turned to the south again. It blew strongly and it soon reached 20 knots. However, it didn’t last long. Less than two hours later, it barely reached 8, 9 knots.

We lifted anchor and started to sail 18 miles to Laguna, Santa Catarina’s last port if you are going southwards.

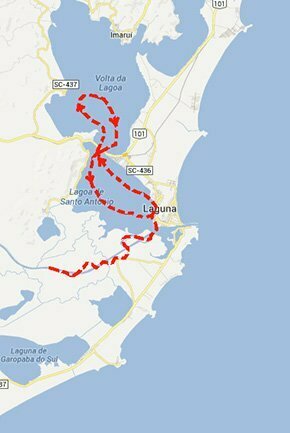

All the way along the coast line is a sandy rope, a reef which protects a series of internal lagoons from Imbituba to Laguna. The first one is Mirim Lagoon, and then comes Imauri’s which finally leads to Santo Antonio lagoon where the city of Laguna is.

On the external part, there are beaches, few of them with dunes, and a few islands. The north coast of Santa Catarina is like the Southeast (Espirito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo). There is basically a couple of small and medium size bays, the Sea Mountain is in the back. You also find estuaries with mangroves.

However, from the south end of Santa Catarina Island, the delicate design is replaced by abrupt and savage forms which are typical in similar latitudes when the coast is hit by stronger elements. That’s the reason why the defenses must change. We are progressively closer to austral and Antarctic seas; cold fronts come exactly from this area. This explains why mangroves and subtle beaches were replaced by continuous strips of sand and reefs with prominent dunes around; there are also ends projected into the sea. Tabuleiro mountains’ remarkable high contours break the monotonous coast line behind.

It’s all live green. It is amazingly beautiful.

At about eleven a.m., we entered through Laguna’s sea

wall from Mar Grosso beach.

As usual, the beginning is frightening. Big waves from different directions look as if they were going to break. Some of them actually do, over the rocks on the south side of the sea wall; however, it is possible to come on the other side. Here the landscape is different from those we are familiar with. On one side, there are flooded areas and in the back sharp hills. On the other, you see the city and contiguous slums. We will explore the area a bit more tomorrow. Today, we have just had time to go down to the historical center near the Yacht Club where we are anchored. We shot and took pictures of beautiful old buildings. Laguna was founded over three hundred years ago.

It is ten to ten p.m. From time to time I come here and add one more line or paragraph to the text. The night is delicious. The northeast wind is back again and started to blow. The sky has cleared up, there is fresh and clean air.

But it is enough. Tomorrow we will have a local guide to go up the Tubarao River, one of the most important which flows here. We made an appointment tomorrow at 8 a.m. at the pier.

Sunday, 25 – 02 – 2007.

We fetched Seu Nilson early in the morning and started our journey. We went up the Tubarao River with the support boat for almost an hour and a half. It was narrow and sinuous in the past, and then, at the end of the seventies, its course was changed (due to floods). And then it became large and straight like a canal. It was dragged several times. We arrived at Capavari district and on our way we passed by Jorge Lacerda Thermoelectric power-station on its banks, one of the biggest (482 thousand kW) which operates burning steam charcoal.

The entire bay of Tubarao is affected, devastated not only by the charcoal extraction waste and processing, which is a frequent activity in the south of Santa Catarina, but also by industrial pollution. The color of the water is milky brown and on the banks, most of the ciliary forest was replaced by pasture and shrimp breeding farms (there are between eight and ten, but they are not operating today due to the “white spot” virus, a typical disease which devastated this culture).

The most immediate consequence is the decrease of non-industrial fishing.

In spite of being a very rich ecosystem where Imauri/Mirim/Santo Antonio lagoon complex is, ordinarily an important fish and crustacean breeding place; today, the non-industrial fishing is limited. Just a few fishermen are seen in the lagoons or river. Most fishermen throw their circular fishing nets from the bank where slums are often seen.

“Povos e Aguas”, a book written by Antonio Carlos Diegues, which we have already mentioned, helps us to understand the situation. On the Human Population Data you will find that “in 2000 the population goes to urban centers, especially to the cities of Imbituba and Ararangua, whose urbanization rates were 96.7% and 82.3% respectively”. One more revealing fact is that in the six districts around the lagoon complex “less than 1.4% of their homes have waste system (2000)”. It is an indigestible cocktail: charcoal (a fossil fuel highly pollutant from the moment it is extracted) exploration is a significant activity in this area. There has been an important migration in the last years. One of the biggest thermoelectric power-stations is on the banks of the main river. Tourism has been developed. As usual, the infrastructure of the cities is a rumbling fiasco. Who is mainly affected? In addition to children who still die of diarrhea, traditional populations, the environment and the diversity of the species also suffer.

Nothing new on the front…

Monday, 26 – 02 – 2007.

This morning our means of transportation was a car. We had not only to visit Santa Marta Cape, where one of the most emblematic and remarkable lighthouses of the Brazilian coast is, but also to shoot the interior of Imbituba. We also wanted to go near Rio Grande do Sul’s border, the district of Ararangua, where our sailboat cannot be anchored since there isn’t any type of protection or harbor on the coast. In this type of situation, car is the only possible way to reach the area.

Santa Marta Cape was our first stop. It is a beautiful promontory surrounded by beaches and where the lighthouse was built.

The view from the top is wonderful. However, on the hills around real estate speculation can be found. Hundreds of houses were built hurriedly, with no infrastructure and go up the dunes around. And all this has happened in the last 20 years. Is this degradation fair in such a short period of time? This is one more sensitive area where there should be no buildings. The sand of the beach eroded by the waves receives an additional amount of sediments from the dunes. This is the dynamic balance we have already mentioned. However, it was partially blocked by this new suburb which emerges from the speculators’ greediness and the omission of the city administration. It is pitiful to see such a beautiful and different area to be reduced to so little.

And then we went to Imbituba, about 30 kilometers to the north, to shoot images of plants of ceramics which represent a great pressure due to the prohibitive extraction of clay, sand, limestone and kaolin, among other things (Imbituba lives on port activities due to charcoal and ceramics). We also intended to talk to environmentalist Jose Truda Palazzo Junior who founded Projeto Baleia Jubarte (Jubarte Whale Project) and Brazil’s representative of the International Whaling Committee. He lives in Imbituba. We couldn’t meet him. He had probably gone to a meeting of this international agency.

Once this task was over, we continued our journey but in the opposite direction, southwards, about a hundred kilometers until Ararangua. I had received a few e-mails from TV viewers denouncing irregular occupation, pollution and obstruction of the river and even a new canal to the mouth of the river which had been opened.

With burning heat we took BR 101, the coastal road we had already used to shoot scenes for programs on the Northeast and Southeast.

We stopped at about 3 p.m. to have lunch. And then we drove for half an hour.

At first we went to Conventos Hill, a high strategic place, a rocky hill at the top of which you see the beach with dunes and the mouth of the Ararangua river. This is certainly one of the most beautiful landscapes of Santa Catarina’s coast.

The river snakes through a green valley up to the beach and then it turns northwards when its course flows parallel with the sand strip along 500 meters. And then it turns right, crosses the beach and reaches the sea.

Ararangua’s pollution is worse in the area of Criciuma where there are big charcoal mines. The water used to wash the mineral, that is “dangerous waste”, is thrown into the Ararangua River. To make things worse, the river flows through an area of big cultures of rice which uses lots of herbicides and pesticides.

Additionally, the district’s fast urbanization and the chronic lack of investments in basic sanitation cause invariably high pollution.

Tuesday, 27 – 02 – 2007.

This trip will be shorter than the others. After finishing shooting and interviewing people here, I intended to take the Endless Sea to Rio Grande, the next port, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul 300 miles down.

I talked to our meteorologist, Joselia Pegorim, to know if there is any cold front coming up. It took us about two days to arrive here and since the coast is dangerous, without any shelter, low and straight, if a southeast wind blows strongly bringing cold masses, there is the risk of being thrown on the beach. We will not deliberately run this type of risk at the end of our journey.

Joselia told us that there will be a soft cold front tonight, however on Friday there will be a stronger one on the same direction.

I decided to leave the boat here. The northeast wind is stronger and sometimes there are strong chaotic blasts. The backstays which hold the mast whistle due to the action of the strong wind. Tomorrow the moon changes. Two additional signs of the natural cycles warning us that “the thing” is coming. We will return with good weather to finish this last long part of our journey.

During these last episodes I was very surprised with two things: first, apparently Santa Catarina’s population is indifferent towards the predatory occupation caused above all by the real estate speculation on the coastal zone; second, the low rate of basic sanitation in Santa Catarina. This is especially due to the fact that this state has Brazil’s second highest HDR (Human Development Rate), the first one is Brasilia (0.844) and the third one is São Paulo (0.820).

I don’t see NGOs complain. I read many articles and watched TV programs on Santa Catarina’s coast and I don’t think the media is interested in this issue. I was astonished when I heard a shrimp farm foreman say that “we got the larvae from UNISUL ((Santa Catarina’s South University), in Camboriu as well as from the Northeast”. This means that in this part of SC’s coast, the university participates in an activity condemned all over the world and it is inspected even by local Ibama, according to CEPSUL’s analyst, Ana Maria Torres Rodrigues, in Itajai.

The lack of coordination of these two important state agencies, the omission of the city administration which “very often disrespect environmental laws” (Ana Maria Torres Rodrigues, CEPSUL’s environmental analyst), increasing tourism, rapid and chaotic growth as well as the torpor of the population seem to be the basic ingredients of the recipe we have tasted.

This is an old problem in Santa Catarina. The forests of araucarias are gone and, in 2006, the Atlas of S.O.S. Atlantic Forest NGO showed Parana and Santa Catarina as the two states which devastated the most this important biome.

It was a bitter surprise to me to realize now the devastation of the coast. The reassuring aspect is that programs like ours which record facts instead of laudation and interview professors and researchers who have given their opinion since Belem, represent a little but anyhow sincere contribution.

We still have time to see our occupation model on a different perspective. The model we have adopted in most beaches has already proven to be a failure.

All of us are responsible. The Earth is our home and this is our country. Each one of us has his/her own responsibility. It’s useless to blame W. Bush. This time we can’t put the blame on Americans for having raped Brazil’s coastal zone.

Don’t doubt this is the reality. Don’t underestimate your share of responsibility.