Saturday, 28 – 01 – 2006.

During this trip, besides Alonso, Agis and Cardozo, our crew has two “reinforcements”: my sons Luis and Jose, aged 10 and 8 respectively. They haven’t sailed for over a year since the sailboat was in the North where the first programs were recorded. Therefore, during the past year I promised to bring them on their vacation. This is the right time. I warned the crew before coming and said there would be additional work. I couldn’t refuse it.

In 2005, I spent half of the year in the boat and many times my absence caused feelings of incomprehension. After returning from a holiday, when I met them, I was told by someone who had asked José, the youngest, if he used to see his father’s TV program and his answer was very clear: “No, I don’t like to see it. The program took my father away from me.” Luis, the eldest, didn’t react differently, in spite of being old enough to understand my new work. Anyway, the fact of being constantly absent made him suffer. That’s the reason why we agreed they would participate in one of the trips and since they are on vacation, time has come to bring them.

We unpacked our things in the boat, had dinner and then went to bed. Tomorrow, we are going to Fort Beach again to shoot the young turtles being released since we weren’t able to do it last time.

Sunday, 29 – 01 – 2006.

We arrived at about 11. I was confused again squeezed in that urban agglomeration where a house in one of the richest condominiums, O Condomínio dos Pescadores, may cost between 700 and 800 thousand reais. In spite of being expensive, it is surrounded by many other houses, one right next to the other. This is so serious that a biologist from Tamar who followed us said that the rent of a tiny apartment with a small room is no less than 800 reais per month! Real estate speculation reaches records here daily. There is such an eagerness to make money that buying property today to resell it for a much higher price two or three months later became an interesting deal… There is a frenetic rhythm of building and occupation. There are fashion stores everywhere. It reminds us of densely occupied beaches in Rio and São Paulo such as Buzios and Guaruja. Likewise, Fort Beach is near the capital, 60 kilometers away from it and it is becoming more and more an option for the weekends, summer houses, buses full of tourists who come for the day, etc… Inevitable.

We walked along Tamar’s facilities which have tanks with almost all types of important fishes in the area. Luis was disappointed because he was looking forward to seeing morays and they had been removed. At the end of the day, when the sun is weaker, we went by car to a place at the beach which was almost desert in order to release the young turtles.

Luis and Jose loved it. Tamar’s guides, Carlos and Paulo, let the boys release the turtles and they enjoyed it a lot.

In my last logbook I said that I would make more comments on Tamar during this trip because it is worthwhile knowing it. It deserves high praise. Moreover, I don’t want to be unfair since I constantly criticize Ibama. But let’s start at the beginning, it’s a long story. It all began in the South, in Rio Grande, more precisely, at the Oceanography College of the University of Rio Grande, at the end of the seventies and the beginning of the eighties. At that time, a few advanced students from Rio Grande, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro dreamed of seeing each inch of the Brazilian coast which was almost virgin and very little studied. They ended by going to Fernando de Noronha, Abrolhos and Atol das Rocas. On Atol they saw something that was so impressive that the idea of creating Tamar Project was born. One morning a few students woke up and saw strange traces on the sand. They couldn’t find out the cause but that night they saw the fishermen, who had taken them, go down to the Atol and kill eleven turtles. It was a shocking scene and caused a strong impact. Most of them were seeing a marine turtle for the first time.

There was an increasing number of sponsored expeditions during which a lot of information and data were collected. Pictures were taken and videos were recorded. Some of them terribly shocking like the one showing the death of the turtles on the Atol or others where fishermen were using young sea gulls as bait for lobster. Something had to be done. That’s how at the South College, the protecting germ of the maritime ecosystem was born among students and their mentors. Up to that moment, authorities were exclusively in charge of national parks and terrestrial ecosystems. This is just more evidence of the neglectful attitude towards the maritime space, which I have already warned about. Putting it in a few words: during the trips, members of that College group ended by showing the need of creating Atol das Rocas’ Biological Reserve (1979), Fernando de Noronha’s National Park (1988), Abrolhos Maritime National Park as well as the need to carry out the first survey on turtles’ spawning on the Brazilian coast. At the same time, a fish census was put into practice.

After contacting authorities in Brasilia to avoid all the red tape, Maria Tereza Jorge Padua, one of the participants of the trips, helped by an uncountable number of people including Admiral Ibsen Gusmão, a well known environmentalist, obtained funds through the IBDF (The Brazilian Institute of Reforestation) for all those institutions as well as to create The Peixe-boi Project, Tamar Project, and others.

During this period of time, biologist Guy Marcovaldi was hired to carry out the survey on turtles and José Catuetê de Albuquerque to study peixes-boi. They were the embryos of these two excellence islands created within Ibama. I will explain how they work tomorrow.

Monday, 30 – 01 – 2006.

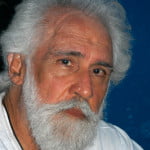

Today early in the morning we interviewed Pangea NGO’s researchers who carry out a lot of studies in All Saints Bay where they work with non-industrial fishermen. Afterwards, we had an appointment with Bahiatursa’s president to talk about mass tourism on Bahia’s coast but we arrived late. We will have to make a new appointment. We spent almost all morning with Pangea’s people. After the interview we gave the rental car back, went to the supermarket and rushed to the boat in order to arrive during daylight at Itaparica island, the biggest of the bay, where we had to interview Portuguese professor and anthropologist, Pedro Agostinho, who has been living for a long time in Brazil and wrote the book “Reconcavo’s vessels – a study of origins.”

We arrived on time. At four p.m. we anchored at Bom Despacho bay near Mar Grande where the house was. We had a wonderful conversation.

Pedro is Judite Cortesão’s foster-son, a person who is very well-known and admired by environmentalists and whose father is Jaime Cortesão, a remarkable historian who wrote fundamental books on the period of the great discoveries. Pedro started the conversation telling us about the moment during which his mother and grandfather left Portugal because of a revolution and went to Spain in the middle of the Civil War. In Spain, Jaime Cortesão was mistaken for a German spy and arrested by the international brigades which took them to the “wall”. The remarkable writer was miraculously saved at the last minute when he was eventually recognized. Afterwards, father and daughter undertook a new and cinematographic escape from Spain and crossed the Pyrenees on foot to seek refuge in France.

From the civil wars we went to the Reconcavo, when the conversation reached at last the subject that had given origin to the interview, that is, Bahia’s traditional boats, especially the Saveiro. Pedro is both an expert and fond of it but he is angry about the fact that there are very few.

I asked him about the old debate which tries to elucidate the origin of the Saveiro. Some say it comes from Portugal, others say it is from India, the Portuguese brought it from there. This thesis is supported by Lev Smarcevisky, an architect from Bahia who wrote “Graminho – a alma do Saveiro” (Marking gauge – the soul of the Saveiro).

Pedro praises several aspects of the book but disagrees with the ideas mentioned in the chapter on the origin and he explains which items must be emphasized in similar studies: the hull and the style of the sails. Then he talked about the tradition of Indian and Arabic boats whose hull is sewed whereas those from Portugal like the Saveiros use nails and wooden tacks. This is enough to elucidate about the origin of the Saveiros: there is no doubt it is Portuguese. In regard to the style of the sails, Pedro says that the feather type Saveiros, for instance, are similar to those used in caravels (lateen sails, known as bastardas, triangular) which used Muslim techniques, known all over the Mediterranean and brought to the Iberian peninsula in the 7th century after it was invaded.

It was a wonderful interview. Pedro showed great erudition and expertise when he talked about Reconcavo’s traditional boats and those of the Brazilian coast in general. He also talked brilliantly about important studies on this subject. He promised to correct and launch his own book again, or a “short study”, as he prefers to call it. He also mentioned topics in Smarcevisky’s book which he disagrees or admires. One another classic is “An essay on Brazil’s Indian Naval Constructions”, published at the end of the 19th century by Admiral Antonio Alves Camara. He only disagrees with the system used to name the vessels and he often praised its virtues.

It was a very pleasant conversation in the courtyard of the house where he was and I finished it because there wasn’t enough daylight.

We returned to the Endless Sea anchored in a bay beside Mar Grande, it was already dark.

Now I will talk about the Tamar issue. I have already said how they hired two students from the Oceanography College to carry out a survey at the beaches on the spawning of maritime turtles on the Brazilian coast in the eighties. At that time, very little was known about these animals in Brazil. After many trips with scarce funds, some of them on foot, riding horses, after sending questionnaires to city halls, universities and IBDF’s regional headquarters, results came up. Then five out of the world’s seven types of maritime turtles were found in Brazil spawning from the north of Rio de Janeiro to the Oiapoque River, the border with the French Guyana.

Guy and Neca Marcovaldi arrived at Fort Beach in 1982, and they were supported by businessman Klaus Peters, the owner of the land of that area. Helped by Klaus, the Navy of Brazil granted them an area of 10 thousand square meters where there was a garrison in charge of Garcia D’Avila Lighthouse. The first incubation enclosure was built there as well as tanks for the recovery of animals.

Guy and Neca spent all the year at Fort Beach, thus little by little fishermen started to rely on them and participate in the project. Later, after comparing the results of Fort Beach with that of other bases, especially Pirambu’s, Sergipe, and Regencia’s, Espirito Santo, it was obvious that to obtain the same results, the teams had to live in the area all the year and deal with local problems and needs. And this was done. Today, a trainee who wants to participate in the project has to live in the chosen area at least for six months to experience the difficulties and try to find solutions with the local community. Maybe this simple decision was the most important one since it made fishermen and their families share the same goals: to generate income, to have a better standard of living and to preserve the environment. The Tamar Base itself at Fort Beach and the fact of being well-known helped to turn that area into an ecological tourism pole thus generating jobs and making local economy more dynamic. Another good idea was enabling more people to work with crafts, especially made by fishermen’s wives and children. The original strategy suggested they should work at the beaches where tourists don’t go and sell their work at the beaches where tourists usually go. The total amount should be given to the community where crafts were made since its members don’t benefit from the money resulting from tourism.

In 1989, IBDF was extinguished and it was replaced by Ibama – Brazilian Environment and Natural Resources Institute). Tamar is linked to the Wild Life department of Ibama’s Ecosystems Board. Its main sponsor is Petrobras. Today, there are 21 research and protection bases covering an area of approximately a thousand kilometers of beaches alongside eight states of the Brazilian coast. There are over 400 employees; most of them are fishermen and inhabitants of villages where the bases are. Tamar promotes environmental education as well as social integration and develops alternative income sources aiming at self-sustainability. The conservation model which was adopted brought international credibility and partnership with important scientific and environmentalist entities.

It is a good example, like the Peixe-Boi Project which is based on the same principles.

Tuesday, 31 – 01 – 2006.

As soon as we woke up, we went to Ponta de Itaparica, in the north, where the Marina which has been recently built is. We anchored our sailboat beside English, African and Brazilian sailboats. Two of Pangea’s employees were waiting for us to take us to a few communities they work with and to get information on the virtues and problems of that area.

Our first stop was Baiacu village where we interviewed a fisherman, seu Mario, satisfied with the fish processing unit which will be soon inaugurated by Pangea. This unit will enable them to add value to the production, consequently they will sell better for a more realistic price getting rid of the intermediaries. Seu Mario told us about the problems caused by those who use bombs to fish in All Saints Bay, they are “outcomers”. People from the community know the problems it causes and they would never do that. According to Seu Mario, this is the main problem All Saints Bay faces today, seeing that the companies on the Reconcavo’s banks “don’t throw chemical products in the water any more.”

Actually, this is a traditional activity not only in All Saints Bay but also in Camamu Bay, which is southwards. People who explode bombs destroy everything around. Not only animal life is destroyed, vegetal and mineral lives are destroyed as well. There is such a big devastation that the area becomes sterile, without life, seeing that even after a long period of time there is no food to attract fishes. But that’s not all. The use of bombs often mutilates people or even kills them and it is considered a federal crime. There is a greater danger here since the bottom of All Saints Bay is full of tubes from petrochemical companies which can be broken at any time causing very serious damages. Pangea distributes booklets containing this information in several communities in order to diminish this criminal action. Nevertheless, this foolishness persists and it is practiced almost daily.

Afterwards, we went to Ponta Grossa where mollusk digging by fishermen’s women is an important activity. According to Max Stern from Bahia Pesca, it is estimated that 10 thousand women live from this activity in All Saints Bay. On Itaparica Island, 80% of local inhabitants live from fishing and mollusk digging; the rest is either unemployed or works in petrochemical companies. Pangea estimates that there are 500 thousand fishermen in All Saints Bay and approximately three million people live in surrounding areas.

We went a little bit further and arrived at the former Matarandiba Island, “former” because there is a Dow Chemical manufacturing unit on the island, the mangrove area was filled with earth and this small island is linked today to Itaparica through a land arm. This was done by the company in order to bring the equipment, cars and trucks closer to the area where gem salt is extracted, one of the raw materials of the caustic soda produced by Dow Chemical. If this damage was caused, we must say that this is also one of the best villages we have seen in terms of public services offered and with better houses.

The last stop of our ride was Cacha Prego at the south end of the island, a beautiful and picturesque fishing community which is on the banks of a river-arm surrounded by wonderful mangroves where there are non-industrial shipyards still operating. This tip was given Pedro Agostinho, since he knew I wanted to talk to Saveiros’ constructors.

We looked for seu Denico’s courtyard, a talkative, joyful and nice Bahiano. In his courtyard, there were the skeletons of two Saveiros, not very big, whose construction had been interrupted by Ibama. Felling is prohibited by this Institute, in spite of the fact that this is the only way of continuing their activity, a tradition and to contribute to perpetuate this Brazilian cultural asset.

It is a pity. Whereas real criminals keep on devastating the Amazon or the Cerrado without punishment, traditional communities are submitted to strict laws. Ibama’s inspectors are merciless. We were already told during this trip by local inhabitants: Ibama doesn’t allow them to earn their bread and butter. Again weak people pay for the powerful.

During our trip from the north to the south end of the island, we passed by areas where there used to be shrimp farms. Our Pangea’s guides didn’t explain why they weren’t operating any more. I asked about the problems caused and Geraldinho, one of the guides, said that a cousin of his who worked on the farm was seriously intoxicated because of chemical products abusively used in the breeding. In addition to this problem, Itaparica Island as well as several areas of All Saints Bay have slums in certain villages and condominiums on shoals and other protected areas. However, in regard to building in permanent preservation areas, Ibama seems impotent.

We returned to the boat at the Marina and slept there. Tomorrow we will go up the Paraguaçu River and continue the Saveiros’ route. These boats were in charge of transportation from these islands of this huge gulf, farms and villages and the Reconcavo’s surrounding cities to Salvador.

Wednesday, 01 – 02 – 2006.

As soon as we left, we saw from afar the Saveiro’s square sail, unique. It was sailing from the south of Itaparica, alongside the coast to go up the Paraguaçu River. We went closer to shoot and take pictures. Unfortunately, it was one of the boats from which the quarterdeck was removed to turn it into a barge to carry sand and stones, a final try at finding an economic value able to generate enough income to keep them operating. Afterwards, we went to the mouth of the Paraguaçu River, a few miles further.

This river’s origin is at the Diamantina Plateau; it flows to All Saints Bay and is its main river. A few miles up the river, Petrobras’s dockyard can be seen and then Salamina, an old fortified farm. After sailing a couple of miles, we arrived at Maragogipe, our first stop where we will spend the night. Tomorrow, we will shoot an old settlement of houses of the city, and then we will go to Cachoeira (Waterfall). The boys are attracting my attention. They love to swim. Like all children, they have lots of energy. They jump from the prow, swim to the stern and go up again and repeat this dozens of times. Always calling me.

Thursday, 02 – 02 – 2006.

We left the boat early in the morning and shot takes of the city. At lunch time, when we were ready to continue the trip, the reversing mechanism broke again. This time it was not the motor’s fitting disc like it happened in the Oiapoque River, almost a year ago. Alonso checked it and found there was water mixed with oil; it is a sign that the heat exchanger was ruined. When this happens, there isn’t the slightest chance of repairing it on board. We will have to find an alternative to go to Cachoeira (Waterfall). It is better to leave the boat and see what we can find.

Well, it was not easy, but we rented a small motor boat to continue the trip. Luis and Jose came with us.

On the way, we passed by São Francisco’s convent built on the Paraguaçu River banks, imposing and magnificent, showing the evidence of this area in the early times of colonization.

A little bit further, the width of the gutter of the Paraguaçu River

decreases and the vegetation gets sparse, turning the area rich in Atlantic Forest into pasture for cattle. Even the mangrove area which surrounds the bed of the river gets so small that there is only a row of trees that are not spared by the cattle. Obviously, this change from forest into pasture obstructs the bed of the river forming sometimes sand islands in the middle of the canal. It was better not to come with the Endless Sea; we would have grounded several times. What was really hard was to convince Jose that there was no “waterfall” where he could swim, but only a historical city to visit.

He didn’t like it at all…

We eventually arrived and could shoot the beautiful buildings, churches, tiny streets and alleys of another historical city of the Reconcavo. At the end of the day we returned to Maragogipe by car and the kids had time to swim and to enjoy themselves competing in a stern motor boat to see who the best pilot was.

We went to bed early. Tomorrow we have to return to Salvador with our sails only. Actually, we will take the Saveiros’ route.

Friday, 3 – 02 – 2006.

At 9.30 a.m. we suspended the direction towards Salvador. A few minutes earlier, the third original Saveiro, “Ventania II”, which was anchored at Maragogipe, was going to the capital too. We could see two of them from afar coming from Cachoeira, taking advantage of the tide and the winds. Hurray!, we will at least sail beside them.

As we passed by Salamina farm, the flotilla approached us. It was a sort of regatta between the Endless Sea and the traditional boats with their huge sails. The Saveiros‘ sails are amazingly big. The most amazing fact is to see that the mast is not supported by a rope. It is the only sailboat I know, I mean the old ones, whose mast is not supported by wires. It is unbelievable! The masts can “reach more than 20 meters and weigh more than a ton”, according to Lev Smarceviski’s book, it doesn’t collapse because of the construction technique, since “they are implanted with a steep slope towards the vessel’s stern and are protected by their own weight.” Additionally, the quality and the flexibility of the wood are other factors that collaborate to support the masts. According to Smarcevisky, “the perfect hydrodynamics of the hull, integrated to the rigging and the sail plan, is the main factor that preserves the whole system.” Smarceviski’s study is quite interesting and he shows that the greatest risk of a broken mast occurs paradoxically when the boat is anchored and the sails are furled. In this case, “even with short and rhythmic waves, the movement of the mast can consequently start a growing swinging and break.”

Smarceviski describes the hoisting sail saveiro: “With a high mast to sail in rivers and sea arms, a great sail area with gaff for superior winds over banks of high vegetation. These sails are based on the Jaht of Dutch origin adapted to the saveiros during Reconcavo’s Dutch occupation”.

Actually, the Endless Sea was left behind by Ventania II, and even if we had an adequate crew, I don’t think we would sail faster in the river due to its bigger sail area. Besides, it was easy to notice that the master of that boat was very skillful. He left all the others behind, developed a higher speed and maneuvered faster.

Despite all that, we really enjoyed sailing beside these wonderful boats.

In the bay, out of the mouth of the Paraguaçu River, each of us took our destination and little by little they disappeared from our view.

There was the delightful sailing to Salvador left, in spite of being apprehensive. If we hadn’t had any problem with the reversing mechanism, we would have gone to São Francisco do Conde, Santo Amaro, Ilha da Mare and Aratu sub-bay. Our original plan was to stay at least two additional days in order to shoot two new programs. We will have to be satisfied with just one which was on the Saveiros’ route. Next time, we will finish what was still missing and go down southwards. See you.