Thursday, 27 – 07 – 2006.

We have been on land for years. You probably saw the date of the previous logbook and realized that our last trip on the state of Rio’s north coast ended on May 17th. We are about to start our 22nd trip two months later. This hasn’t been the rule. Since we started our TV program, our routine has been half month on board and 10, 12 days in São Paulo, and then a new trip again. It’s been really hard. It was different this time. TV Cultura repeated all the episodes on Bahia in June. Consequently, we decided to rest and submit the Endless Sea to a check-up. Here we are again. Thank God! I was able to go through all the red tape involving the production of a TV series. Believe me, it’s a lot of work. From the outside, television is something marvelous; working with it is complex and huge. It wouldn’t be easy anywhere. It deals with ego and vanity; and it is extremely powerful; people are influenced by TV, but above all it makes people known. If it is a Foundation, such as TV Cultura in São Paulo, things are even more peculiar.

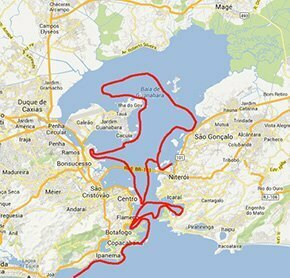

What really counts now is to be again on board the Endless Sea in Rio de Janeiro’s Yacht Club. During this trip, we intend to record two TV programs; one on the Bay of Guanabara, and the other on the city of Rio de Janeiro.

As soon as we arrived this afternoon, we went to IPHAN’s headquarters to have a wonderful lesson on Brazil’s history; with special emphasis on Rio’s architecture and urbanism, given by Claudia Girão, a sweet architect and plastic artist. She spoke to us about different changes which have occurred in Rio since Americo Vespucio baptized the city in 1501: the foundation by Estacio de Sa at Fora Beach, Brazil’s capital in 1763, the changes made by the Royal Family in 1808 in the Imperial period, the proclamation of Republic, the Federal capital; always emphasizing the physical and architectural changes caused by each period. Our first day couldn’t be better. Claudia loves history and public patrimony; she is also talented and patient and explains everything in the slightest detail.

When we were getting back to the Endless Sea, it was “exciting” to be in the middle of shots between the police and bandits in the financial center of Rio. We also saw injured people bleeding on the chest just beside our car going to a police car.

We arrived on board late. We had a shower at the Yacht Club and went to bed. We will start to shoot tomorrow early in the morning.

Friday, 28 – 07 – 2006.

We went to the Botanic Gardens to shoot the park founded by Don Joao VI and talk to the researchers of the institute where many studies are carried out including the DNA of the Atlantic Forest’s plants.

We were welcomed by historian and researcher Begonha Bediaga. During our talk she minimized the interest of the king in botany specifically. She emphasized the fact that his main concern was the foundation of the gunpowder manufacturing plant in that specific place. He wanted to protect himself from the French who had expelled him from Portugal and had promised to chase him even here, south of the equator. Begonha said that in the neighborhood of the gunpowder plant “Don João decided to plant a few trees”, far from where he lived – São Cristovão – due to poor technology of those times, “explosions of that sort were commonly seen in plants like that”. Begonha’s thesis is interesting. She thinks that Don João was quite smart, “after all he was the only European crowned head who was not attached to the French; he escaped and came to Brazil, was able to protect himself and returned later when he recovered the Portuguese throne”.

According to her, the famous imperial palm trees planted by the monarch were some “sort of retaliation” since “they are native trees from the (old) France Island, currently the Reunion Islands, a French possession in the Indian Ocean from where the trees were stolen by the Portuguese”. As you can see, bio-piracy is not a recent activity, on the contrary. In those times it was important to look for plants which contributed to the economical viability of the new colonies and stealing seeds or cuttings was a common practice. Coffee, for instance, came to Brazil as a stolen cutting in the baggage of Francisco Palheta from Para (commanded by the Portuguese) who stole them from French Guyana. It was the same with the Cayenne cane whose origin is explained by the name itself: it comes from Cayenne which is also in French Guyana. We were able to remove some vegetal richness from other countries, but our richness was also stolen. We all know that the rubber tree cuttings from the Amazon were stolen by the English and planted in Asia. The following chapter, according to the teachings of History, shows that later the rubber extraction richness which boomed the economy of Belem and Manaus collapsed and wasn’t able to compete in the international market; thus one more Brazilian economic cycle based on extraction ended.

After the interview, we shot beautiful images of the magnificent Botanic Gardens with more than four thousand planted species in an area of 157 hectares. A wonderful view. Centennial trees, giant ceiba trees, lakes, ruins of the old gunpowder plant, birds of different species, squirrels, the famous palm trees; an amazing “island” of animal and vegetal life in the middle of the metropolis.

Before leaving, we spoke to researcher Sergio Ricardo Cardoso who works in the Protaxon project in the field of taxonomy and intends to create a base of native species’ genes, that is, to define and store (in powerful freezers) the greatest amount of DNA of Atlantic Forest’s plants, the only research of the sort carried out in Brazil.

After having lunch right there in the famous Hippodrome restaurant; we went to the other end of the city, in the north, in search of Quinta da Boa Vista in São Cristovão, where the National Museum is today, the former King’s palace. It is unnecessary to say that we got lost several times and arrived an hour later. But we were able to shoot. Mission fulfilled. We returned to the Yacht Club early in the evening.

When we arrived, we saw there were several sailing friends we had met on our journey. They were the participants of the East Coast Cruise, a fleet of sailboats from Rio, Sao Paulo and other southern states who were preparing themselves to start sailing to Recife. They will be participating in the next REFENO, the Recife-Fernando de Noronha regatta which takes place every year in September. There were about 40 sailboats.

We were told by one of the participants that a cold front was coming with strong wind, rain and polar coldness and it would probably arrive here during the first hours of Sunday. Therefore, I decided to change plans. Instead of shooting historical points of the city, tomorrow we are going to the sea. We must try to register Rio’s shore and part of the Bay of Guanabara with good weather. We will leave very early in the morning.

Saturday, 29 – 07 – 2006.

It was still dark when Alonso started the motor of the Endless Sea and sailed out of the bay, towards the south end of Ipanema beach, near the Tijucas Islands. We started to shoot scenes of the shore from that point in order to show to TV viewers the extent of man’s interference in regard to the destruction of Rio de Janeiro’s millenary, exuberant and famous coast. When I decided to get up, after having sailed for an hour, with swollen eyes due to sleep hours, I could see the marvelous scene: the sun rising behind the mountain chain, the reddish sky and the still undefined contours of the city on the horizon. From the distant sea, you don’t realize immediately how big or high the buildings are, or the lack of space between one block and the other. You don’t even see the slums climbing on the hills. You can only see the magnificent geographical line of this part of the Brazilian coast. It’s easy to understand why travelers who arrived by boat were amazed at the beauty of the landscape. Actually, the view of all those peaks is fantastic; each one with a particular shape, the slopes covered with the Atlantic Forest and the rocky walls which fall abruptly in the sea are impressive.

However, as the sailboat approaches, the subtle and tenuous contours are clearer. Little by little the idyllic scenery turns into something macabre and huge slums are seen climbing up the steep slopes of the hills higher and higher, one hut right next to the other, like a row of working ants. They also devastate whatever is found on their way: the same forest which “held” and made those slopes beautiful hundreds of years ago. An announced tragedy. In this case it is an environmental crime, a desperate cry, the absence of the hand of the State. Brazil’s drama. Today, there are six million, five hundred thousand and thirty-five people living in slums in Brazil, 16,8% live here in Rio de Janeiro (source: Ibope/IPP). This is not an exception. According to UN data, there are two billion people living in slums all over the world. This is a very serious situation and so deliberately accepted that it is outrageous. The number 11 objective of the Millenium Development Goals is to improve the standard of living of at least 100 million people who live in slums until 2020. Monitoring progresses or not, but with this goal in mind, the UN created the slum index. According to French economist and urbanist Yves Cabannes from Harvard University and international consultant in public policies, urbanism and popular housing, there are five indexes: “inadequate access to water and basic sanitation, lack of infrastructure, poor quality housing, overpopulation and lack of legal agrarian rules.” And he adds: “this common denominator is important and helps the UN in the assessment of the progresses achieved by the Millenium Development” (FSP – 12 –02 – 2006).

Well, this is the first dramatic situation we see as we approach the coast. And still astonished to see how huge the problem is and the difficulty to approach the coast, buildings started to emerge. They are high and wide, one right next to the other and quite near the sea. They result from real estate speculation and chaotic growth. This is the evident proof of the unfair and unequal income distribution and now they grab your attention first. In the past your attention was grabbed by the beaches. In fact, if you arrive by boat, they can hardly be seen. You have to approach dangerously just before the waves break and then you can see the white sand of Rio de Janeiro’s beaches. This is absurd; Paraiba’s Constitution is missing here…

After we sailed alongside Rio’s shore, we entered into the bay. We stopped at

Fora Beach where the first part of the city was founded by Estacio de Sa in 1565 in order to shoot for the program; and then we sailed towards Santa Cruz Fort, on the east side of the bay where Niteroi is.

From there we entered in Jurujuba’s creek towards Niteroi’s Yacht Club whose name is Sailing. We wanted to visit and pay homage to a remarkable family devoted to the art of navigation: the Schmidt-Graels, whose today’s most famous members are brothers Torben and Lars. Yes, in a country where football reigns, sailing is the sport which brought more Olympic and world championships’ medals to Brazil and they are two of our greatest champions, besides Robert Scheidt. We met Moema and Ingrid Schmidt, aunt and cousin, as well as Torben, Axel and Lars’ mother. We drank gin tonic with them and had a nice talk. I was also given the miniature of a draft made by master Jose Alberto, whose nickname is Teachar (the pronunciation is “Titcha”) from Serra Grande, in the south of Bahia, a gift sent by Anders Schmidt who had met us in Canavieiras, Bahia, (see logbook nº18).

But we had a lot more to shoot. We didn’t stay long enough.

We continued to sail towards Fiscal Island. On our way we saw an old tugboat “Laurindo Pitta” from the Brazilian Navy, completely restored, beautiful and imposing, on a tourism route around the bay. Lots of pictures were taken (see site) before we arrived at the famous island where the last ball of the empire period took place. There we shot again and then sailed alongside the platform of the port and saw huge frigates of the Brazilian Navy anchored as well as the Aerodrome-Ship from São Paulo a giant from the War Navy. Then we passed under the Rio-Niteroi bridge and sailed to the Fundão Island. We saw in the back of the bay a sad scene: some sort of cemetery of ships. Huge hulls, some of them with the deck up, old, abandoned, heeling and rusted waiting for death. Since dismantling is expensive, they are left there awaiting some sort of disaster to disintegrate completely causing one more ecological problem in the badly treated Guanabara Bay.

At the Fundão Island we saw more horror scenes. There is so much pollution in this part (the west side) that it is possible to see fishermen removing the fishing net at the beach with three shrimps, a crab, a tennis shoe, several glasses and lots of plastic bags. Outrageous. Unfortunately, this scene was registered and the fisherman was interviewed. Time to go back to the Yacht Club. When we got back, we had two surprises: wonderful pasta prepared by Alonso and the Embratel’s maritime mobile service warning on “Rio-Radio” station that at the height of Paranagua the cold front was blowing at a strength of 7 and 8 (about 50 knots). This means the beginning of a hurricane. How nice to be in the port, in a sheltered bay, when alarming warnings like these echo on the waves of the radio. Thank God we are here. I had hardly thanked our luck when wind strokes arrived. Weak rain and cold reigned in the atmosphere.

I had lunch in the cabin, went to bed and slept before we arrived at the Yacht Club.

Sunday, 30 – 07 – 2006.

Since there was bad weather, we decided to walk around the city with a guide in order to shoot churches, palaces and historical sites: Ladeira da Misericordia (the Mercy slope), the Promenade, the Imperial Palace, São Bento, Outeiro da Gloria (Gloria hillock) and Candelaria. Lapa and the arches, mysteries and bohemian legends. Santa Tereza and its Portuguese charm. It was possible to see how beautiful the city was before the demographic boom in the 20th century. We devoted the whole day to this task. It was late in the afternoon when we had lunch in Copacabana, at Marios, a very well known barbecue place at the end of the beach. We returned to the Endless Sea in the early evening.

Monday, 31 – 07 – 2006.

Today we had a nice day starting by the breakfast prepared by Alonso: pancakes with honey and jam. Afterwards we went to Copacabana, Post 6, where one of the last non-industrial fishing colonies of Rio’s metropolitan area is. We also saw the last canoe made of wood which was built over 70 years ago and it is still operating (see pictures on the site). It was very exciting.. Fortunately, we met the head of the colony, Ricardo Mantovani who like the other fishermen had not gone fishing because of the strong tide. It was a wonderful interview. Lucid and aware of the situation, Ricardo pointed out the most important issues from fishermen’s perspective: too much pollution. Ricardo gets very angry when he puts the blame on ships which clean bulks and containers in the bay. This makes the situation worse since nobody wants to buy fish “having the smell of diesel oil”. Additionally, there is the unfair competition with huge fishing boats which enter in the bay and use their nets. We saw one of these boats release one rubber boat to catch fish in Rio’s Yacht Club’s area (see pictures). Ricardo complained about the lack of union in fishermen’s community due to the fact that most of them don’t have a legal situation. The vast majority is semi-illiterate and unable to have legal papers due to governmental red tape. Therefore, in spite of the fact of having fished for over thirty years, some of them have no working rights and are unable to retire.” He also said: “depollution is not successful; it is a pity to see the lack of perseverance of our authorities.” And he jumps to the following conclusion: “Chaotic growth, waste thrown directly in the estuary and in the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon; the amount of garbage on the surface when you enter in the bay scares me; it is like the end of times. If things continue like that, I don’t think I’d like to have a sun in the fishing activity. He won’t be able to survive.” Do I have to say anything else?

Before the end of the interview, we talked about the canoe. Yes, it is the last one made of tree trunks still operating in this area. Is it possible to fish with it in the bay, I asked: “No, it goes to the sea.” How old is it? Ricardo didn’t hesitate: “Over 70 years”, and he shows us a newspaper picture with a legend saying that it served as barricade to tenants during the Fort Rebellion, in 1922. Unbelievable! In fact, it was the same beautiful canoe which with its glorious and fishing past was still there in front of us ready to go to the sea again. This is one more proof of the Brazilian excellence in the navigation art. It is a pity that just very few people know that and praise this centennial tradition.

We finished our morning task brilliantly. We decided to have lunch right there in a bar on the beach and wait for Mariella Camardelli Uzeda, an agronomist engineer who has a PhD in Natural Resources, works for BioAtlantic NGO and will make us visit this afternoon the Guanabara Bay Institute at Niteroi’s Botanic Gardens. We went there after lunch. This NGO’s headquarters is right in the middle of the Botanic Gardens. In the surroundings it is partly covered with the Atlantic Forest: all types of ferns, huge trees, climbers, wonderful.

The Guanabara Bay Institute is coordinated by Dora Hess de Negreiros, a nice lady who was FEEMA’s participant in the nineties. Inspired by Sao Paulo’s Tiete River depollution program and the fresh memory of Eco-92, this movement was launched in Rio (in 1993) with the aim of depolluting the Bay of Guananbara.

Dora left FEEMA during the second period of Brizola’s administration and she has tried since then to work for BioAtlantic NGO in the production and diffusion of information on this issue. She also participates in official forums such as the Management Committee of the Guanabara Bay, an agency connected with the government of the state (there has been no meeting since the beginning of Rosinha Mateus’ administration in 2003).

She told us that since the movement was launched; a study has been carried out helped by Japanese technicians who had participated in Tokyo’s bay cleaning program. Once the diagnosis was done, IADB (Interamerican Development Bank) and the Japanese Bank of International Cooperation financed part of the program; over 800 million dollars for the first part of the project, with the counterpart of the state administration (the first estimate for the entire project was 4 billion dollars).

The project is known as “Depollution Program of the Bay of Guanabara” aimed at treating about 60% of the waste thrown in the bay, a rate that hardly reaches 25%. After so many years, not even the first phase was achieved.

Obviously, the results aren’t encouraging. “Nine million people live in the surroundings of the bay and there are two refineries in it: Duque de Caxias, from Petrobras, inaugurated in 1961, and a private one from Peixoto de Castro Group. Three ports, several shipyards as well as thousands of illegal mechanics’ shops, domestic waste thrown in nature (15 thousand liters per second, daily, according to Eliane Canedo de Freitas Pinheiro, who wrote the book “The Bay of Guanabara”, an expert in Ecology and Environmental Planning), thousands of polluting cars, obstruction of rivers, chaotic occupation of hydrographic bays and 16 districts around it. It is too much.”

“Works start and stop. There is no continuity with successive administrations. Many districts out of the sixteen have no piped water. If there is no piped water, domestic waste cannot be treated”, she says.

Dora also points out insane decisions taken by the state authorities such as the treatment plant, Estação da Alegria (Joy Station)”which is being built to meet Rio’s North Zone needs alongside Linha Vermelha. It never ends, it has been built for 10 years”, she says upset. Dora explains to us that in the past the main problem the Bay of Guanabara had was industrial pollution, since many companies which were in the area were from the forties and fifties; consequently there was no modern technology. Today, the main problem is garbage and untreated waste.

Figures are enormous: 12 thousand tons of garbage from the neighboring sanitary filled land. It is estimated that 16 districts produce approximately 450 tons of waste which go to a specific destination: the same bay. There is also oil leakage from diffuse pollution resulting from Rio’s car fleet as well as from occasional accidents in the refinery of Duque de Caxias, sometimes caused by ships and boats (the last oil leakage caused by Petrobras occurred in 2000 when approximately one million two thousand liters of oil leaked…).

There are also a few tons of heavy metals from industrial effluents. An unmerciful environmental massacre.

I asked about public opinion’s pressure, the role played by different NGOs and the press. She answered discouragingly: “The environmentalist movement fight one against the other for models and paths to be followed. All of them want to be the child’s father and bring it up according to their own principles. The press helps very little and this makes people uninterested on this issue.”

It’s really tough! The situation in Rio is different from the Tiete River depollution in São Paulo. At that time there was Eldorado Radio Station which was permanently in campaign and watching everything. It was also backed up by Estadão (SP’s newspaper): We were always requiring measures, changes and denouncing negligence, environmentalists were able to give their opinion as well as the notable.

This story is worth being told; after all everything started with it. We had just hired a new journalism director, Marco Antonio Gomes, who arrived to shake everything up and put an end to the bureaucratic spirit which existed at that time. The first measure I asked him to take was to give up the official routine and work on new matters. Marco and the editorial staff got together for several days. And then he came out with many ideas. One of them was to have a program on the pollution of the Tiete River a subject that was ignored by SP’s press. At that time the issues were the devastation of the Atlantic Forest, chaos in the Amazon, the end of the meadow, air pollution, etc. Not a single line on the Tiete River which had become an open air waste. The program was designed in an interesting and unusual way. As part of our team went up the Tiete River by boat to show its degrading situation; London BBC’s team (with whom we had an operational agreement) went down the Thames River to describe the actions taken to depollute the English river; showing that when London’s public opinion got together and required solutions, public authorities reacted and many years later the river was depolluted. This was the motto of the program: the power of the public opinion and the ability to make public authorities act. It was a boom on the air. The program had hardly ended and hundreds of people started to call to give their opinion, to contribute and suggest mobilization. I couldn’t work for many days. I spent days talking to radio listeners, schools, class associations. Even a police headquarters’ chief came to Eldorado Radio Station “to give money to the campaign”. But there wasn’t any campaign, just a radio program. It had echoed so extraordinarily that I asked for a NGO’s help, the SOS Mata-Atlântica, headed at that time by João Paulo Capobianco. I told him what was going on. Capô, this is how he was called, was excited about it; however, he said that his organization only dealt with the forest and couldn’t be in charge of such a big and polemic cause. There were no funds nor experts, etc. Anyhow, he was going to talk about the issue with the Advice Board. A few days later he called me and said categorically that if I could get funds, his organization would accept the challenge. We figured out costs and tried to get funds. After a while, I got funds of 350 thousand dollars from Unibanco. At that time (1991) it was the most significant donation given by the private initiative to environmental causes. This amount of money would allow Núcleo União Pró-Tietê operate for three years and after that period of time the organization would have to find funds by itself. This is what actually happened. SOS Mata-Atlântica accepted Eldorado and the listeners’ challenge. Mario Mantovani was invited to head Núcleo and mobilize public opinion, which he effectively did. In a little while, there was a petition (the most important ever done in the country for issues of the sort) with one million two hundred thousand signatures, almost 10% of SP’s population supported it showing solidarity and indignation. And then government authorities reacted to the pressure of public opinion. Mario Covas invested one billion dollars in the first phase. Alckmin about the same amount in the second phase. It was the biggest basic sanitation work ever undertaken in Brazil. Now comes the third phase. But there has been a great improvement. More than 90% of the 1250 polluting companies identified by SABESP (SP’s agency in charge of water treatment and supply) started to use philters. There is no new industrial pollution any more. Thousands of streams were piped and treatment plants were built. The Tiete River gutter was dragged and deepened. Now SP’s population has to be taught, like Rio’s, to stop throwing cigarette ends, old pieces of furniture, tires, big amounts of plastic and all types of garbage. Despite everything, São Paulo’s case has been successful. The population has to be watchful and require of the next administration the beginning and the end of the last and third depollution phase. I am particularly happy for having participated in this civic movement since I had the opportunity at that time to be the director of Eldorado Radio Station. This movement has not only achieved its goals since it started fifteen years ago (1990); it has also influenced that of the Bay of Guanabara, according to what was confirmed by Dora Hess (as well as that which intended to depollute the Guaiba River). When we get in the south of Brazil, I will check the situation, but as far as I know, it is not doing very well…

At the end of the day, we had the good feeling of having fulfilled our duty. Tomorrow morning we will visit the hydrographic bay of the Guapi and Macacu Rivers, one of the only sources of the Guanabara Bay which is not yet polluted. We want to catch people’s attention to the bad aspects, but we also insist on showing the good ones.

Tuesday, 01 – 08 – 2006.

This morning we welcomed on board the team of Super-tudo, a program of RJ’s TVE, who wanted to interview us to show the backstage of the Endless Sea program. Now our program is broadcast by TVE which broadcasts programs for several educational TV channels all over Brazil. TVE didn’t hesitate in accepting our program. Three prime times were chosen to broadcast the program: on Fridays at 7:30 p.m. It is broadcast again on Sundays at 10.30 p.m. and on Saturdays at 2.30 p.m.

The whole morning we talked about our trips, the difficult situations we had to face, the wonderful landscapes, negligence, lack of surveillance, as well as the various problems found.

They finished after midday. We had lunch at Rio’s Yacht Club and waited for our friend Mariella Camardelli Uzêda from BioAtlantic NGO who would follow us.

Afterwards we went towards Friburgo, in RJ’s mountains. Cachoeiras de Macacu is about 100 kilometers far from Rio. On the way we saw an area of seas of hills (in geology this expression is used to describe an area which is relatively flat with hills having the shape of the half of an orange) with some secondary forest at the top. Mariella told us that in the past people used to live at the top to escape from inundations of the lowlands. As time went by, they started to come down and the forest we have now has regenerated. And then, in the forties, most rivers which flow into the Bay of Guanabara were submitted to changes in their courses in order to drain the flooded areas; consequently ordinary diseases such as malaria, paludism and others could decrease. The result was catastrophic: obstruction increased a lot and with it new inundations occurred quite often. This may make people go to the top of the hills again and devastate again the little coverage left.

Mariella is an agronomist engineer who has a PhD in Natural Resources and is in charge of, among other things, creating the management plan for the APA (area of environmental protection) of the Macacu River Bay. It was her idea to take us there where the Tres Picos State Park is, the biggest UC (Conservation Unit) of the state, with 46.350 hectares corresponding to the area of five districts: Teresópolis, Guapimirim, Cachoeiras de Macacu, Nova Friburgo and Silva Jardim.

We arrived at about three p.m. and the upper we went, the worse the weather. Fog, light rain, cold. All this caused by the arrival of the cold front I have already mentioned. What a pity. With this type of weather it is difficult to have good images to shoot.

We were welcomed by Flavio Luiz de Castro Jesus, park administrator. He explained to us that the greatest problems he faces are hunting, heart of palm extraction, fires, most of them caused by Candomble and Umbanda’s activities (witchcraft involving candles) illegal property and uncontrolled tourism.

Then she took us to the Macacu River Bay, a beautiful place with crystalline water going down the mountains on a rocky bed, forming rapids, small wells, waterfalls and cascades with the beautiful Atlantic Forest around. We recorded an interview with him, and continued on the path until we arrived at a very special place, amazing, where an imposing jequitiba-rosa of approximately a thousand years and 40 meters high took our breath away (see pictures). Impressive. We were astonished to see such a great live marvel, stuck into the ground on the slope of the mountain, 400 meters above the sea level. It was getting dark and still raining; we stayed there nevertheless admiring that unprecedented beauty.

I tried to imagine how the Atlantic Forest was before the arrival of the Portuguese; consequently when devastation started. I had rarely felt the emotion I was feeling beside that magnificent millennial tree.

We went back to Rio with that gigantic image in our minds. This has been one of the most beautiful moments the Endless Sea team has had since we started the trip at the Oiapoque River, more than a year ago.

Wednesday, 02 – 08 – 2006.

Back to the sea again. This time we sailed to the back of the Guanaabara Bay, almost 15 miles inside it, behind the Governador Island. We wanted to reach the mouth of the Iguaçu and Sarapui Rivers, two of the most polluted rivers with tons of garbage floating on fetid waters. The weather was bad, cold and rainy. We continued sailing until the gauge of the sailboat allowed us, that is a meter and eighty centimeters. We anchored three miles away from the mouth. From that point on the only possible way was the stern motor boat. The southwest wind was strong for the small boat. Sailing between 15 and 18 knots, it formed waves that made our progress difficult. Bad weather also made visibility difficult. We couldn’t see the coast and this didn’t allow us to identify remarkable points. Film maker Cardozo and I had to put rain clothes on, however after having sailed for half an hour, we were completely wet and cold. Our equipment was in hermetically closed bags to avoid sprinkles from the waves as well as rain water. We could see huge spots of a strange color from afar in the middle of the vegetation which was formed before by mangroves and native forest.

They were slums, this national plague, especially here in Rio de Janeiro. According to economist Ricardo Paes de Barros from IPEA (Institute of Applied Economic Researches): Rio has too many slums for the importance of its economy. There are poorer states with fewer slums.” (O Estado de São Paulo, Supplement Cities, 12 – 02 – 2006). Cariocas (inhabitants from Rio) watch out: you can’t go on like this. You cannot loose your ability to express indignation. When this happens there is no other possible change.

When we were getting closer to the coast, we saw a fisherman. We asked him about the mouth of the rivers and he showed us the wrong direction. We sailed for about 40 minutes until we found another fishing boat which showed us the right direction. We were sailing in the wrong direction!

This mistake allowed us to see a canoe moved by cloth, probably one of the last and the only one we saw during this trip. It was made of wood, as usual, with a marlinspike sail. In spite of the agitated sea, it sailed perfectly, loaded by fishing equipment, nets and so on; and it was also tugging another boat! How nice to see a sail-canoe, in the 21st century, sailing in the middle of the Bay of Guanabara. I thanked the fisherman who told us the wrong direction. I wouldn’t have witnessed this view of the past, if he hadn’t told us the wrong direction.

It took us between 30 and 40 minutes to reach the entrance of the canal. Was it the mouth of the Iguaçu River? I entered in it to check it out. It was the Reduque canal, open by Petrobras’ refinery, very dirty. The thin mangrove on its banks was full of plastic bags; it takes almost a century to get rid of this material. We entered in it and shot the damages caused by progress, with refinery tanks where there were mangroves before. Company guards waved their hands trying to intimidate us. They made nervous signs, screamed things we couldn’t understand; however, we understood very soon what they wanted to say: “Get out of here!”

We ignored their appeal and continued up to the moment the stern motor broke down. There was no other choice. Paddling against the wind and the current, impossible; we had to ask to be tugged at the port of the company. Several guards hurried and in a very authoritative manner they took note of our names and asked why we were there. When we identified ourselves and said we were press people from TVE and TV Cultura, they slowed down and changed the tone of the voice. Thanks God! We were spared.

Fortunately, a boat which renders services for Petrobras was leaving the canal towards the bay and tugged us to the Endless Sea. The mouth of the river was about 200 meters from the point we had entered. What a pity! We weren’t able to shoot those shameful images which result from negligence of state authorities, the lack of initiative by Rio’s environmental agencies and chaotic growth. The little daylight left was vanishing and we decided to return to the Yacht Club. This was the end of our adventure in the Bay of Guanabara.

Thursday, 03 – 08 – 2006.

Today we shot more scenes for the program on the city of Rio de Janeiro. There were some parts of the city we had not yet visited such as Gavea, Barra, where the city grows, with condominiums, shopping centers having names in English, slums as usual, and pinus which was planted to replace the beautiful Chapéu-de-Sol . Even here, in Rio, these damned ugly trees replace our rich biodiversity. In Barra, these trees were planted by the public administration in the middle of the avenue. This is the end!

At the end of the afternoon we said good-bye to Alonso and the Endless Sea and caught a plane to São Paulo. It was the end of this trip. Next time we will go to Restinga da Marambaia and then Angra dos Reis. See you!