Sunday – 08 – 01 – 2006

We arrived in Salvador last night. Agis and Cardozo came with me. We just had time to unpack our luggage and arrange it on board the Endless Sea anchored at Bahia Marina. My sailboat is brand new after the hull and the broadside were painted and some work was done. It is very good to know that we can always count on the boat, even after the long marathon from Oiapoque to Bahia, after having left more than three thousand miles behind. We satisfied our yearning for the sailboat and our adventures. We also talked a lot to our friend Alonso Góes who was expecting us on board. We went to bed at last. We left the boat in the morning to shoot the Modelo Market. In addition to shooting the hullabaloo made by hundreds of stands selling different types of handicraft with tourists peering every square centimeter, we talked to several people in order to have more information on the last saveiros (a type of lighter) which still navigate in All Saints Bay. We were told that one of these boats still comes every week on Thursday evening to unload goods on Friday morning. Fine. On the scheduled day we will be standing here in position to record this fantastic traditional boat which is part of Bahia’s history and was immortalized in Jorge Amado’s novels. It is amazing how fast the Saveiro disappeared. I came to Salvador to participate in a regatta in 1986. At that time I saw a famous saveiro race, João das Botas regatta, which takes place every year in January. There were over a hundred boats of different types and sizes; ranging from the feather type with one and two masts and the sails that remind us of a bird’s feather, to the heaving sail type, which are heavier. It was wonderful. When I returned to Bahia again, I had a good camera and I wanted exclusively to take pictures of those historical boats. This was in 1997. Disappointingly, there were only 18 still operating.

Saveiros were predominant in the Recôncavo (coastal region of the state of Bahia). For approximately 400 years, these boats reigned in this landscape going up and down the rivers that flowed into the Bay on whose banks the city of Salvador was built; bringing and taking people and goods to the Modelo Market and making the scenery even more beautiful. When the roads were paved in the 70’s and 80’s, trucks won the competition; at the same time the children of those who had built and navigated the saveiros felt discouraged to follow the same hard profession. There were fewer orders, idle shipyards were closed and saveiros were replaced by motor boats. Little by little the elegant and rustic saveiros, an important part of our historical patrimony, started to disappear. Today, only three of the original saveiros remain in Salvador’s waters. There are about 12 without the quarterdeck which was removed to turn saveiros into simple barges appropriate to carry exclusively cement and stones. We were told that there are saveiros in Camamu, anyway there are just a few and they are about to disappear. This is the reason why we cannot miss the opportunity of recording them in their noblest function. Talking to the right people on the pier and getting information about where Bahia’s remaining saveiros are made me happy.

From Modelo Market we went to the historical center, Pelourinho, to shoot the buildings, mansions and churches for the program we intend to make on Salvador. This is one of Brazil’s historical cities like São Luis, in Maranhão, Olinda, in Pernambuco, recorded by UNESCO as Humanity’s Patrimony. We returned to the Endless Sea in the early evening. We had a good shower at the Marina without saving water which is usually necessary on board, and then we had dinner and went to bed.

When I was in bed, I enjoyed the fact that at least half a dozen people very simple and humble congratulated us on the TV program. When they saw us, they crossed the street to ask if we were actually the Endless Sea team and after confirming it they congratulated us on the approach we had chosen, with no “glamour”, showing things as they are with the good and bad sides, and wished us a good stay in Bahia. What could be better than that for a first day?

Monday, 09 – 01 – 2006.

Today, at 8 a.m., we were at the door of the office of Bahia Pesca’s president ( a company of Bahia’s government), Max Magalhães Stern, who I was looking forward to talk to. It is always wise to try to understand both sides of an issue. In this case, I wanted to know what had made Bahia’s government invest so much in crustacean culture, this plague that ruins the northeastern coast with a devastating impetus. We also talked about other issues. In Bahia, there are from 70 to a thousand fishermen spread in 73 colonies and 99% are non-industrial. Trawl-net fishing is one of the activities as well as the unbelievable fishing with explosives which is still commonly seen in the All Saints and Camamu Bays, believe it or not. How is this fishing made? Like in war, these madcap fishermen explode with dynamite part of these rivers or bays killing all types of life. Then they collect what comes to the surface… Along one thousand and two hundred kilometers of Bahia’s coast there are approximately a hundred ports where fish can be unloaded and the most important ones are: Caravelas, Prado and Alcobaça, all of them in the south of the state. This is not accidental. This is where Abrolhos is with its fantastic and huge coral bank. As I have already said in previous logbooks, this ecosystem is so rich in marine life, sheltering more than 25% of the species, that it is compared to tropical forests due to the biodiversity.

The great amount of fishermen and the outstanding area it occupies make Bahia the forth Brazilian fishing state and to your astonishment the production has increased. According to Max Stern, between 2000 and 2004, the loaded volume has increased 15%. Your attention please: the fishing boats storage capacity has not increased; it is the fishing effort, consequently the productivity that has increased. As far as natural maritime resources are concerned, Bahia is also the forth largest shrimp producing state. I don’t know how long Bahia will hold the forth position. I guess for a short period of time. According to what was shown in Piaui and Ceara’s logbooks, the storage of this crustacean is rapidly destroying the sustainable fishing due to harmful practices such as compressed air, nets, overfishing, dragging, coastal pollution, capturing species below the minimum size, etc. Bahia’s shrimp banks are obviously found on the south coast since that’s where corals are also found abundantly.

I asked Max Stern about trawl-net fishing, which is normally used here three miles away from the coast, especially to catch shrimp. I also insisted on telling him about the talks I had in colonies on the Brazilian coast where most people acknowledge how harmful it is and worse than that, they know that if they continue to do so very soon nothing else will be fished. Whenever we talk about trawl-net fishing, fishermen say unanimously: “to change we must count on the government’s help and support, after all this has been our bread and butter for generations.” But if we want to obtain effective results, investments in research are necessary. This has been said by several university experts in this subject. But this doesn’t happen. Unfortunately, we are one of the developing countries with the lowest research investment rates.

As far as the trawl-net fishing is concerned, Max acknowledged the great impact on the maritime environment but he said eagerly that “Bahia has been working with the Federal Government so that the fisherman changes this activity. We have already made suggestions on this issue,” he concluded. He was not very convincing, but I quote his words anyway. When I asked about fishing with explosives he was not happy, but he said that it was quite impossible to avoid it. “Unfortunately, it is a tradition that will hardly end.” Afterwards he talked about the actions undertaken in aquiculture, especially about the tilapia-breeding developed both in the continent and in estuary areas.

Tilapias in salty water? I didn’t know. This worries me, after all this is an exotic species, consequently isn’t it dangerous to introduce it into the maritime ecosystem? Whenever I read about it or interview experts they warn about the danger of introducing exotic animals in ecosystems, regardless of the species, without a thorough study carried out previously. There may be disastrous consequences such as Tejus in Fernando de Noronha whose mission was to exterminate rats, but since they were taken to the island they have only eaten turtle eggs (see FN’s logbook), or other similar problems, such as capybaras and deer on the Anchieta Island, on São Paulo’s north coast, and many others. Careless about this issue, Max spoke about the settlement of farms in Cairu, Taperoa and Valença. According to him, fishes are bred in cages and tanks. I froze. Are these tanks built in mangrove areas like in shrimp farms? To answer all these questions, I asked for official help to visit these areas during our next trips and Bahia Pesca’s president agreed with my request. As far as I am concerned, I intend to go back to Bahia’s Federal University to talk to biologists. As soon as I get more information, I’ll talk about this issue again. So far, we have just been informed about this new activity and we were told that the production has been significant: 1500 kilos per year, per cage or tank. In the same area, there are a few oyster farms held by the company which we intend to visit too.

After these issues we talked at last about shrimp farms. Obviously, Max Stern supported the government strategy and tried to minimize, sometimes to deny the damaging effects. He repeated the speech about generating 3.7 jobs per hectare which is stated in a study carried out by a few Northeastern teachers supported by the Shrimp Breeders’ Association, ABCC. (This polemical study was mentioned in Ceara and Rio Grande do Norte’s logbook). But every time he mentioned an argument, I replied with lots of arguments I have learned, retorting and refuting the breeders’ reasoning. Many times Max could not reply. He looked at me with a forced smile on his lips, having nothing to say, but nodding his head in agreement… Since he is a government man, he must repeat the shrimp breeders’ speech. Max was embarrassed when I said there were government funds, public money, through the Northeast’s Constitutional Fund (FNE). This fund’s guidelines refer to “preference given to micro and small entrepreneurs” and projects that “protect the environment”. When I mentioned these topics, he stared at me with his eyes wide having a perplexed expression, since he had not imagined I had all those details. Then again he had a forced smile. Eventually, he just confirmed Bahia’s strategy, saying that here the government chose four priority breeding areas: Jandaira, Baía de Todos os Santos (All Saints Bay), Canavieiras and Caravelas, with a maximum extension area of ten thousand hectares. Before ending the conversation he said that “there is no economic activity which doesn’t result in environmental impact” and “nobody complains about cotton or soya which devastate pasture flatlands”. In regard to the cultivated shrimp, an exotic species from the Pacific, Max ran through another text he knew by heart, like those kids at Pelourinho who recite data about historical churches and said this wonderful sentence: “it is like nellore cattle which are not from here, but nobody says anything…” He ended the conversation saying that there are 51 shrimp breeders in Bahia, 33 are small, 12 are medium size producers and 6 are big.

Well after the interview with Max Stern, we went to Eugenio de Avila Lins’ office, Bahia’s IPHAN Superintendent. For over an hour, we talked about a variety of details on Salvador’s historical architecture.

On the same day, we interviewed Sara Alves, management coordinator of Bahia’s Conservation units. I was favorably impressed by her seriousness and technical and political competence. In my next logbooks, I will explain the reasons.

Before calling it a day, there was an interview with Marlene Campos Peso Aguiar, the director of the Biology Institute of Bahia’s Federal University. We had a frank and all-embracing talk with all of them and mentioned almost all the aspects that affect Bahia’s coast ecosystems and made comments on public policies concerning the occupation of the coast. It goes without saying that everybody is apprehensive about the shrimp farms issue and astonished with the increase of resorts and mass tourism. We returned to the boat late, tired and astonished with all the information given.

Tuesday, 10 – 01 – 2006.

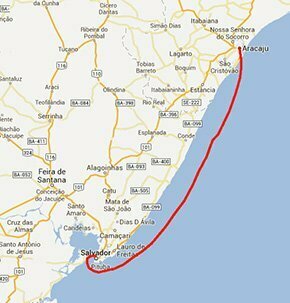

Today we took the car and went to Mangue Seco at Sergipe’s border. We saw on our way vast areas covered by eucalyptuses and pinuses for Camaçari pole where there was Atlantic Forest before… We also visited an organic coconut farm (Nossa Senhora da Conceição) owned by TV viewer friends, José Rabelo and Aline Soares, 20 kilometers away from Sergipe’s border. During this trip, we intend to travel along Bahia’s north coast to record images for the first program we will make on this state. We decided to know more about Lusomar shrimp farm which we had already visited hurriedly during our previous trip.

This time we went by boat to the area where Lusomar throws back into the estuary the water used in breeding tanks. After the shrimps are collected and processed to be exported, the farms throw back the polluted water used in the tanks and with it tons of toxic microorganisms such as metabisulfite or remaining antibiotics used to avoid pests. There is a strong smell and a dark color. Additionally, the water has a thick lay of foam which remains even after it is thrown back into the river. A sad and impressive scene (see pictures). Then we went to Costa Azul Beach to see the larvae breeding unit. Again I was speechless with the size (see pictures) and I could also notice that Lusomar didn’t respect the minimum distance of 300 meters from the high tide line for the first row of buildings inwards according to Conama’s 303 Resolution which tries to discipline the occupation of the beaches. As it is shown on the site photos, part of the works is clearly within the protected limit. The area also has dunes and reefs, both APPs…

In our investigation we found the old swaping practice commonly used in Brazil. Everything makes us think that Paulo Souto financed these works with the Northeast Constitutional Fund (FNE) and in exchange the company had to give funds to a mayor campaign (whose political party is the same) in Jandaira district where the farm is. The former mayor was ACM’s ally (ACM – Antonio Carlos Magalhães, a well known politician from Bahia), current governor’s enemy and political rival… Well, Lusomar did its part and elected a mayor who has a criminal record in Sergipe and is accused of many crimes. I’ll try to find out and talk about it later. “Friends deserve everything, enemies punishment.” Is this the country we live in?

We will sleep at our friends Aline and José Rabelo’s farm tonight.

Wednesday, 11 – 01 – 2006.

After an abundant breakfast which included cuscuz (steamed corn flour meal) and several organic fruits from their farm we left and started our trip back to Salvador. We thought this part of the trip would take us two days but we are going back sooner since the stairs of Nossa Senhora do Bonfim Church will be washed on Thursday and it is one of the most idolized traditions in Bahia. Consequently, we must record it. Instead of covering the entire north coast during one single trip, we will do it in two trips. This time we have just visited a kitchen midden near Conde’s District, in addition to visiting Sauipe Port and the tourism complex nearby which has the same name. Next time we will shoot Fort Beach and the way it changed reminds us of Jericoacoara, in Ceara.

Bahia’s north coast has been recently occupied. It started effectively after the “Green Line” road was built at the end of the 80’s and the beginning of the 90’s. Since the government knew that with the road he was giving the green sign for the occupation, North Coast APA was created.Most of the land of this part of the coast is owned by a few powerful businessmen such as the Barreto de Araujo, Odebrecht’s owners, who also own the area where Sauipe’s tourism complex is; Klaus Peters, who owns more than 20 kilometers of beaches, from the Pojuca River northwards including Fort Beach; and Goes Cohabita, a company that also has many properties in the area. After the road was built, whose name “Green Line” shows there is an environmental concern like everything in the Northeast, the doors for occupation were open wide. Since then mass tourism has increased with dozens of crowded buses from Salvador coming almost everyday and the massive arrival of greedy resorts. Sauipe’s is the first one and it was followed by many others established at Fort Beach and alongside the road such as the Spanish Iberostar. Today, there are several residential condominiums in this area and real estate speculation reigns everywhere.

What can we say about these hotels? What grabs my attention is the fact that they are never completely full. Sauipe, the most famous has about four hundred beds and occupies a maximum of 70% of its capacity. Are so many other hotels really necessary? Bahia has already 28 so-called resorts, according to the magazine Brazilian Resorts Guide, from the On Line Publishing House.

But the fact is that they don’t stop building. Seven other undertakings will be inaugurated or expanded until 2007. I don’t understand. Obviously, the Brazilian coast, especially the Northeastern coast, is one of the world’s most beautiful and untouched coasts, sooner or later tourism would arrive here. And this simple fact would be enough to justify such a great investment. However, sometimes I think about the origin of all the money, especially European, but not only, that has been invested here. I doubt if my reasoning has some basis or if it is just business impetuosity which is something I cannot understand. It also surprises me that the lesson was not learned. When I started this trip I thought that maybe the lesson of the harmful unplanned and predatory occupation that occurred in the Southeast could be avoided in the North and Northeast. But I see it is not true. It is astonishing. Then I think about what my father told me when I was a kid. He always said that if we learned with other people’s mistakes, humanity would be perfect today… Maybe it is just that. Anyway, I think I will interview Bahiatursa’s president to know his opinion on this issue. We must examine what kind of compensation is required by the state government of these undertakings especially in regard to the infrastructure the state is implementing in these areas. By the way, Bahiatursa has to explain many things. Last year, on November 2nd, Carta Capital published an interesting article by Leandro Fortes from Salvador with the following suggestive title: “A duct from Bahia – a ghost account of 101 million reais, ghost expenses and the suspicion of having unreported funds go the rounds of ACM’s voodoo yard.” The article starts by the following lapidary sentence: “Think of something eccentric, unusual, absurd: it has already happened in Bahia” by Otávio Mangabeira, Bahia’s governor in the middle of the 20th century. In the article, Leandro Fortes describes a corrupt practice found out by Pedro Lino, Federal Audit Court’s counselor, similar to that involving Marcos Valério (accused of participating in corruption practices involving PT). Forbes says that Pedro Lino found “strange connections between Propeg, a publicity agency, and NGOs formed by public employees, and Bahiatursa is in the middle of all that.” According to the magazine, “the flow of money reaches 101 million reais, almost twice as much the amount of 55 million reais handled by Valério.”

I would like to make it clear to the reader that I am not the only person who has doubts about the resorts craze. There are also public employees, NGOs and university teachers who have doubts. Supposing Europeans come exclusively to Brazil, it would be difficult anyway to find all the hotels in the Northeast full.

Well, the devastation of the millenary scenic beauty is not the only harm; there are huge cement constructions either at the beach or a little bit away replacing the exuberant natural landscape. It is not only the excessive amount of people that this type of hotel attracts to places which don’t always have the infrastructure needed to welcome them. Sometimes the expectation itself of offering jobs is harmful like that at Sauipe Port which was the victim of an outbreak of uncontrolled migration before the inauguration of a tourism complex caused by the vain life improvement. The result was an increase in the number of inhabitants: traditionally there were five thousand and today there are eight thousand. Obviously, not of all them got a job. But these are not the only problems caused by mass tourism on the fragile coastal zone.

There are also huge open air garbage deposits in order to store the garbage produced by thousands of hotel guests. They don’t even know it since around Sauipe complex, for instance, there are hundreds of colorful litter baskets, very beautiful and politically correct, used to separate recyclable garbage. But there is a problem, after tourists throw paper, plastic and glass in the corresponding baskets a truck comes which mixes and throws everything at the huge garbage deposit on the other side of the paved road, away from the eyes of careless tourists…

Well, we returned to Salvador in the early evening and slept in the boat at the Marina. Tomorrow we will see Bonfim’s washing.

Thursday, 12 – 01 – 2006.

It was difficult but we shot it. There were over a million people in the streets. It was extremely hot and there was very heavy traffic. There was loud music in bars and restaurants all the way long. A few imprudent tourists were robbed. Some people were peeing in the middle of the street… But we shot the celebration. The day was almost entirely devoted to it. In the afternoon, before the end of our activities, we interviewed Renato Cunha, Gamba NGO’s coordinator, probably one of the most important and active pioneers in Bahia (see suggested links). It was fantastic. Renato will help us with lots of contacts with people and institutions operating on the south coast of the state.

Friday, 13 – 01 – 2006.

We spent an entire day shooting Salvador’s historical buildings and waited for an additional crew member, painter Patricia Magano who will join us during this trip. Like in the 18th and 19th centuries when foreign missions came to Brazil and brought among their crew members a painter who was in charge of recording the landscape and habits of the exotic country, we also decided to try to bring on board a painter who, with eyes of the 21st century, intends to record in water-colors the landscape we visit. Maybe later there will be an exhibit of these paintings.

The best part of the day was the morning at the Modelo Market when we were trying to shoot the saveiro which always unloads on Fridays. That’s what we were told.

When we arrived, there was no boat at all. We asked one man who was standing at the quay. Fortunately, we found out he was the saveiro’s master. No they had not come today but the boat was anchored at the quay of São Joaquim market from where it would leave for Recôncavo later. We took saveiro’s master, Jorge, with us in our car to avoid bad luck and arrived together at the quay. After having crossed an open market where everything is sold in tiny little stands one on top of the other, with no hygiene at all, in a burning heat, avoiding carriers who were taking goats with their paws tied up in wheelbarrows, where there were also desperate chickens flapping their wings fearfully, we finally arrived at the sea and I almost fainted. There was not only one, there were two, out of the three which still navigate here. One of the most beautiful I have ever seen was anchored right in front of me, painted with different colors but predominantly blue and turquoise with white, red and live yellow details, “E da Vida”. It was so beautiful with the brand new painting that it took my breath away (see pictures). Honestly, I was not expecting to find a boat so beautifully painted. “Sombra da Lua” was anchored at the sea too with its red mast and green hull. This was the saveiro whose master we had given a ride to. I picked up my camera quickly and started taking a long series of pictures which took me a couple of hours. On E da Vida’s board, there was a passenger who saw me and said in a calm way without raising his voice, as if he already knew me: “Hi, João, I was waiting for you. I knew you were in Bahia… and you would look for a saveiro”. I was astonished. I looked at him to figure out who he was. Maybe an acquaintance but I had forgotten his name… But he introduced himself soon: I always watch your TV program. I like the way you present it, especially your interest for traditional boats”. Then I remembered I am on TV and sometimes when you least expect it, someone recognizes you in the street. This time it was at the quay beside one of Brazil’s most emblematic boats.

We stayed there for a while, talked and checked each detail of the construction. Afterwards, we left and master Jorge went with us by boat to Sombra da Lua where he would embark with his crew members. I wanted to shoot the saveiro raise the sail and sail. The first view we had when we left the quay was the front with its red master a bit crooked, a witness of one of the strongest popular culture traditions but which is unfortunately not very much recognized by most Brazilians. Seeing it was wonderful. Very calmly, no need to talk to the other crew members, each one took his position and started the maneuvers. The huge sail was raised slowly while the man who was at the rudder was heading for Itaparica. Then the sail blew up and the elegant and rustic saveiro with perfect shapes and proportions started to speed up. A few minutes later it started to disappear on the horizon. Mission accomplished.

Saturday, 14 – 01 – 2006.

In the morning we said good-bye to Alonso and Patricia who were going to stay on board so that she could paint some scenes of All Saints Bay and we went to Carmo’s Convent which is a hotel today. We wanted to record it since it is probably Salvador’s most beautiful architectural monument. Then we went towards the north coast to finish the program we had started. We went straight to Fort Beach where we arrived at the end of the afternoon. There was light and we went straight to the Tower House, Brazil’s first Portuguese large building. This monument is seen as America’s only feudal castle and it started to be built in 1551 and it was ended 1624. We owe it to Garcia and Francisco Dias D’Avila who came with Thome de Sousa in 1549, Brazil’s first general governor. They introduced cattle in Brazil. Their descendants were the world’s greatest landowners in the 18th century of an area of 800 thousand square kilometers going from Bahia to Maranhão. The ruins are outstanding, especially the chapel contiguous to the building and it has just been restored. The floor and the ceiling are in high relief and at the back of the altar there is a sculpture which reproduces a huge shell in high relief too, spectacular. When I was here in 1984, the chapel had not been restored yet, therefore I couldn’t see all the beauty of the monument. Congratulations Garcia D’Avila Foundation which takes care of this historical patrimony whose stones were stuck with a sort of mortar made of whale oil and fat, among other materials (see pictures).

Afterwards we chose one pousada out of a hundred to spend the night and avoid wasting time the following morning. We have lots of things to do. We will talk to Jubarte Whale Project’s team whose current headquarters are here, then we will have a meeting with Tamar people, created in 1988, whose national headquarters are at Fort Beach. We also have to show how unplanned urbanization and real estate speculation, highly dense population as well as mass tourism and several resorts which were built in the same area of the coast turned this beautiful part of Bahia’s coast into an area of high middle class slum houses. I don’t know which recent change has shocked me the most during this trip. Jericoacoara, in Ceara, Pipa Beach, in Rio Grande do Norte, which have experienced the same situation, or Fort Beach. Anyway, it is too much for one single day. It is better to go to bed early.

Sunday, 15 – 01 – 2006.

My cell phone rang at 7 a.m. I picked it up a little bit dizzy since I was asleep. I recognized Paulina’s distressed and anxious voice. I had barely answered the phone and she said a torrent of words: ”João, I’m scared. It is crazy! I don’t believe it, take note: Jandaira’s mayor is Herbert Maia, from PDT. He has two Taxpayer Identification Numbers and a long criminal record. He was sued 5 times by Alagoas’ courts, 41 times by Sergipes’s courts and 11 times by the Federal Audit Court. He is involved in false notes’ issuing, stealing and dismantling cars and in crimes. In 1988, he was arrested in Sergipe. Be careful!”

I was not really astonished! I was expecting something like that; after all, we have seen many small Brazilian coastal cities’ mayors who only take advantage of the voters’ good faith. It was like this in Jeri, Ceara, in Aracati, Ceara, where the mayor is the owner of the largest shrimp farm, Compescal, which surrounds entire communities, intimidates those who complain with threats of death, pollutes local inhabitants’ waters, etc. In Cururupu, Maranhão, I told you about the mayor who “bought” an island as soon as the state government announced the tourism master plan for that region. Jeri’s mayor is Spanish, a real estate speculator who doesn’t even live in the village and whose name no local inhabitant knows how to pronounce, the president of the local community’s inhabitants doesn’t know either. Well there are lots of similar examples. On the north coast of the state of São Paulo, three months after having taken over, Ilhabela’s mayor was one of the partners of a real estate agency which sells forbidden lots that belong to Ilhabela’s State Park, divides river-banks into lots and makes his team buy the Estadão issue at the news-stands every time this newspaper publishes articles showing clearly the mayor’s frauds. The situation was so terrible and the evidences shown by the newspaper so clear that the Public Prosecution Service decided to interfere and deprived Manoel Marcos de Jesus Ferreira of his position. Today he governs the district thanks to an injunction…

After Paulina gave me the record of this hangman disguised in politician, I calmed her down and told her we were not at the border between Bahia and Sergipe where Jandaira District is as well as Lusomar’s farm. I just wanted to confirm a few suspicions and accusations we found out when we were there checking the terrible harm caused by Lusomar, whose stakes are collected by Bahia’s governor, Paulo Souto. Well, here it is. The product of the bargain is Herbert Maia…In addition to all the accusations which have already been mentioned, he was arrested in Sergipe in 1988, accused of being the leader of a gang which sold false notes for several district administrations in the state. According to our investigation, he was involved in death crimes such as Waldir de Freitas Dantas’, Cedro de São João’s public prosecutor. Finally, Herbert was accused by his partner, Cristinaldo Santana, whose nickname is “Veneno” (Poison), of receiving and dismantling stolen cars. All these affairs emerged because of his “victory” during last elections (1797 votes against 1721 votes for the second candidate), thanks to Lusomar’s help, and were published by the Northeast press. When the opponent’s political party asked to refrain Herbert from taking over because of his crimes, reporting judge Antonio Cunha Cavalcanti informed that “on the records of the processes there is a certificate issued by Bahia’s Supreme Court informing that the processes had not yet transited in rem judicatam. Thus I could not supply with provision the appeals.” That’s it. We must thank Bahia’s shrimp breeders for this marvelous contribution.

This was a good start for today. Paulina also said that she had done some research on a series TV Globo started to broadcast a few weeks ago during “Fantastico” (a popular TV program on Sunday evenings). The series name is “The Brazilian Coast” in which all of a sudden TV Globo’s reporters show a great interest on this subject and “explore the coast”, showing scenes in the North and the South in each episode. Paulina was indignant and almost shouting she told me: “João, do you remember Guajerutiua? (a small village on Maranhão’s coast which can be reached only by boat), do you remember the scene which we shot for program number 16?” And she started to describe it in detail. “Yes, Paulina, I remember it very well.” “Fantastico” showed exactly the same thing, the same canoe, from the same angle.” Before I answered, she said: “Do you remember when we were in Maranhão, in Alcântara where we shot such and such scenery? They showed the same thing!”, and she concluded: “man, what a dirty trick! They are copying our program step by step, that’s not fair.” I had to calm her down telling her that on the contrary, it was very good. Better than what I expected. This means we are doing something nice, unheard-of and to say the least very well done. Otherwise, this powerful TV channel would not copy our programs. It was the same when I worked at Eldorado (a radio station). Whenever we had an exclusive material, an important accusation, or any of the topics introduced in daily journalism by the Eldorado Radio, “the big sister” copied it and broadcast it as if it were Globo’s , consequently that was not new. Let’s continue. We have more things to do.

As soon as we left the hotel, we went to Jubarte Whale Project’s headquarters to talk to biologist Clarencio Baracho who makes research with photo identification. According to Baracho, the jubarte whales started to concentrate besides Abrolhos on Bahia’s north coast, especially between Itapoã Beach and Fort Beach. This is the reason why there is another base here. Since then more than three thousand individuals were seen and pictures were taken. The jubarte whales are identified through the pictures of the tails seeing that like the humans’ digital print, the pigmentation of each individual is different and by comparing pictures taken throughout the world, you can learn about the migration routes and their habits through this observation. Clarencio told us that recently one of the whales recorded here at Fort Beach was seen and photographed in South Georgia. This is the reason why he is going to the sub-antarctic archipelago next week with the well known Kotic, Olig Beli’s. Have a nice trip!

During our talk, Clarencio reminded us that the whale fishing in Brazil started in All Saints Bay, in 1603, when these huge animals were not used to the human presence and consequently came gently and abundantly to the bay. We have old engravings showing scenes of hunting near the bar’s lighthouse, in Salvador (see pictures). I’ve already read reports, especially Jean de Lery’s, a shoemaker who came with Villegagnon when he founded the Antarctic France in the Guanabara Bay, in the second half of the 16th century. In his report, Lery writes literally the following: “… resting in this vast and deep river (the Guanabara Bay), (the whales) approached so much the island (Coligny) that it was possible to shoot them with the harquebus.” He continues saying: “However, seeing that their skin is very hard and the fat thick, I don’t think the bullets penetrate and hurt them.”

In Salvador, old houses’ mortar and the illumination of this city as well as that of many Brazilian coastal cities was made with by-products removed from dead whales cut into pieces. Today, as we all know, they are under threat since countries such as Japan, Norway, Iceland and many others don’t respect the world’s moratorium and keep on fishing whales.

Clarencio explained to us how the 2001 tourism observation plan works, when visitors rent a boat and sail followed by a biologist from the project’s team to see the whales. This type of activity is increasing year after year. In 2001, there were seven cruises and seventy tourists. In 2005, the number of cruises was 53 and there were approximately one thousand tourists. This is a world trend, that of observation tourism, at such a point that an American economist figured out that today a live whale yields all over the world about one million dollars per year for those who practice this activity. Here is an excellent proposal for tourism, and it is self-sustainable. I hope our coast will have soon lots of similar activities, after all there are several possibilities with native and migratory birds, mammals, fishes and a great variety of ecosystems which can be visited and known, yielding income and improving the local communities’ standard of living. Additionally, this preservation will bring profit, the only way of perpetuating species, generating jobs, etc.

Fortunately, in regard to whales, Brazil has a proactive posture and supports at the International Commission of Whales the creation of a sanctuary in the South Atlantic where any type of hunting would be prohibited. Every year, during the meetings of the commission, Brazil suggests this idea. Nevertheless the proposal hasn’t got three quarters of the favorable votes which would turn the suggestion into an international agreement. Japan refuses to sign and puts pressure on small countries that depend on its economy to follow its vote.

From there we went to Tamar Project where Gustave Lopez, Regional Coordinator, received us. He explained to us how the project works and in my view it is probably one of Ibama’s only islands of excellency. Apart from the journalist’s impressions, this group of actions must be mentioned since it has already proved to be effective and well planned. It aims at achieving sustainability as well as the improvement of the communities’ standard of living and the preservation of biodiversity.

In the next logbook on The All Saints Bay, I will explain Tamar’s modus operandi in detail since a good action can generate copies when they are diffused on the media and the contribution tends to be even greater. Besides, the journalist is supposed to show the “good side” when there is one. And this is the case here. Now I will just say what it is about, the details you will find in my next logbook. I am just going to report the invasion that occurred at Fort Beach which was extremely exaggerated, the result of the speculation and omission of the public power.

I first came to this beach in 1984 when there was only one pousada and a charming non-industrial fishermen village with simple and honorable houses made of brick and masonry born in the shadow of several centennial native trees, something that rarely occurs on this coast sun-drenched 300 days per year. There are beautiful beaches, rivers, lagoons, coral reefs rich in maritime life which bring food closer, coconut trees, small creeks which were turned into ports for the fishing fleets which in the past sheltered about 30 and 40 saveiros according to the inhabitants we talked to. In the past, according to any inhabitant of a big city, this scenery deserved the definition of “tropical paradise”, so incorrectly used today. Maybe the observer could not notice the persisting poverty problem, the lack of formal jobs, consequently the community’s low income and a life which depends almost exclusively on extraction or subsistence agriculture. After the arrival of BR 101, the coastal road that crosses the country, the occupation started. Again, our authorities didn’t learn or didn’t want to learn with past experience, despite various examples, and didn’t prepare any management or occupation plan before the construction. Consequences brutally affect the area today, it is visible.

To start with, the old village is full of bars and restaurants, dozens of stores, groups of houses, condominiums, and lots of pousadas, small buildings and huge resorts. The distance between one building and another is ridiculous. It is so small that one person between two houses cannot open the arms. I tested it to record one part of the TV program and realized that there isn’t enough room to open both arms. And from one or two small streets of the old village, today’s “urbanization” created many others, some named after important politicians of the state, others baptized with rough marketing criteria which would make scouts blush, names that have nothing to do with the history and the tradition of those who once lived here. This means that those who already knew the village, even old inhabitants lost their references completely. I was astonished during the first hours trying to find where the original village was. Little by little I started to recognize a couple of houses always surrounded by this new world of cement.

I talked to Tamar’s people about it since many of them have been living here for approximately ten years. Gustave, coordinator, told me that the population has increased especially in the last six years. Before, when he walked along the village, he knew and greeted about 80% of the population. “Today I barely recognize 10%.” Obviously, he is worried about the great amount of people, after all the ecosystems here are extremely fragile. Coral reefs, for instance, are stepped by visitors every day, but nobody tells them that this may kill the ecosystem. There are remaining lagoons such as Timentube’s and the areas at the beaches where the turtles spawn. Gustave says that the most difficult thing is to convince the youngest and richest boys who drive on the beaches with buggies and quadricycles. When he tries to warn them about the danger of affecting the turtle eggs, the reply is: “Do you know who you are talking to?” Usually, these young people come from families of politicians or powerful businessmen, and they are not used to obeying orders”, says Gustave. He continues: “in regard to local inhabitants there is a perfect integration, and most of the times they help. With lower class tourists there is also comprehension, but with wealthier people…”

I talked to two traditional inhabitants who were both distrustful of the interview and so joyful that they looked exaggerated. They gave us their opinion. Both think that things are much better today. “Before it took us two days to go to Salvador. We had to take the boat to cross the Pojuca river, whereas today it takes us only one day.” They say there are jobs for everybody. Certain things were polemical such as the pavement of streets which replaced the sand. “Most people didn’t like it. What can we do? That’s life,” said Seu Nicanor. And the houses, where are they, I asked. He answered they had been rented or sold. The fishermen who rented them moved to the other side of the road, in Açuzinho, and sometimes, when the house has to be given back, the tenant refuses to leave. “A few similar cases will be decided in court”, said Seu Nicanor, a former fisherman who is 63 years old, born at Fort Beach. He also complained about the new names of the streets and said that it is confusing for local inhabitants. After having praised the new situation, he contradicted himself and mentioned another problem. He said that many new restaurants and stores don’t accept the entrance of local inhabitants; they don’t even want them to stop at their doors. And when tourists don’t come, he reminds the owners that “native people would never do that”.

We interviewed Seu Nicanor at Praça da Alegria (Joy Square), another new name; in a burning heat since the houses and buildings are so next one to the other that not even the strong wind can penetrate. Absurd. In my walks, I never knew where the sea was, there were too many buildings. Talking to my team about the situation, Agis described the view she had from the window of her room on the second floor of the pousada: “I could only see the roofs, João, one next to the other.” Right after that, I returned to the pousada to take some pictures and shoot, once Cardozo and I had slept on the lower floor and had no idea of the “panoramic” view. Look at the pictures on the site and jump to the conclusion yourselves. All I can say is that I felt as if I were in a shopping center when I was walking along the new village which replaced the old one I knew. Again, I remembered Paraiba’s example whose coast occupation law is in the State Constitution which prohibits this practice (see the corresponding logbook). Is it possible that only Paraiba learned the lesson?

After the interviews with local people, we went to Açuzinho to see living and urbanization conditions. Slums, that’s what I saw. Sewage in open air areas, garbage on the floor, houses with those “new wings” a well known Brazilian solution, unpaved streets, awful (see pictures). Now there are no doubts that this spree on the Brazilian coast helped to feed banking accounts of real estate agents, tourism agencies, stores in general, etc., but local inhabitants, I’m not sure. I don’t know to what extent this change was profitable.

Before going to Salvador, we visited a huge resort that is being built in the area, Iberostar, with 4.600 beds. Please write down: it is on the same beach and it is less than 20 kilometers away from Sauipe complex. Isn’t it strange, or am I dumb? There is something strange in this resort matter.

Acting like this I don’t think we will be able to guarantee that future generations will have the right to enjoy the same natural beauty, which is the biodiversity that still surrounds our horizon.

We returned to Salvador and recorded on our way back the occupation of well known beaches such as Arembepe (very dirty with many beer and soda cans spread on the sand) and Itapoa lagoon with the dunes and the remaining vegetation of the Atlantic Forest. Both places can be considered today as urban areas since they are surrounded by developing cities.

Monday and Tuesday, 16 and 17 – 01 – 2006.

Two days devoted to shooting things in Salvador which hadn’t been recorded yet. We interviewed a few local inhabitants and people who work in the Pelourinho area. But all the time we shot the biggest amount of slums we have seen so far during our journey. The Endless Sea project makes me scrutinize all the areas we have been to. Before, when I traveled as a tourist I only visited the noblest areas and didn’t see the tough reality, although I knew it existed. Now is different. We go everywhere; to the wealthy as well as to the poor areas. It is impossible not to be astonished when you see the great number of slums in Salvador. Everywhere you see the same thing: giant human ghettos. Social exclusion is shocking in spite of the artificial tricks used to make tourists have a good impression. In the city’s tourist areas everything is shining: new pavement, clean streets, bilingual plaques and high standard buildings which are taller and taller. In the neighboring areas the rudest poverty showing the failure of our development model or its perversion, it doesn’t matter.

Wednesday, 18 – 01 – 2006

Early in the morning at 8 a.m. we took the plane to São Paulo. We will be back by the end of the month to record two other programs and continue learning about Bahia. We will know the All Saints Bay (BTS) more in detail. We also intend to go up the Paraguaçu River traveling along the Saveiros’ route. See you.